The history of gaming is distinct, I think, from the history of gaming ideas. Gaming has been such a fragmented hobby that very often people weren’t aware of their peers’ ideas, leading to a lot of reinventing of the wheel. This struck me the other day when I was reading an excerpt from “Designing Modern Strategy Games” by George Phillies and Tom Vasel. Phillies is an old hand from the days of 1960s boardgaming, but what grabbed my attention was not about him, but about someone else. A guy named Sid Sackson. The excerpt below comes from that book. The “I” in the excerpt is Phillies.

Once upon a time, [I] had the good fortune to visit the greatest American board game designer, Sid Sackson, at his New York home. Sackson had by far the largest collection of traditional board games in the world. (He did not collect board wargames.) He estimated to me that he had 20,000 distinct titles. I can confirm that almost every room of his house was filled from floor to ceiling with games, including shelves in the middle of every room except the kitchen. He also had various game fragments, such as the cover of Race to the North Pole, a nineteenth-century game about a race to the North Pole via Montgolfier balloon. The collection was carefully organized, so that he could find whichever game he wanted almost immediately. Sackson’s game library was backed by a set of notebooks, so that when I described design elements of games from my board wargame collection, he rapidly inserted those details into a notebook and indexed them.

I have never heard of Sid Sackson, even though he wrote a column in the 1970s in Strategy & Tactics magazine, and has a Wikipedia page. That is almost certainly my loss. But if someone like me who plays (or at least knows about) a fair number of boardgames has never heard of the greatest American designer of such games, you can at least make an argument that someone should be doing a better job of spreading this information around. Oh, for those notebooks! So many designers were working in a vacuum, oblivious to all the game mechanics Sackson catalogued, reinventing wheels and warp drives.

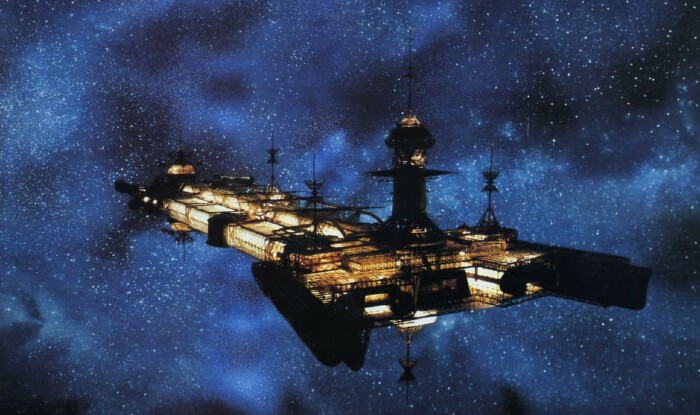

But games do carry a flavor of their time, and picking up a box from thirty years ago can either dissuade you with the musty smell of outdated implementation, or entice you with the allure of imagination. There is a lot of imagination in games about spaceships. One particular one — The Wreck of the BSM Pandora by Jim Dunnigan and Redmond Simonsen — has about equal parts imagination and frustration. For the time, that was probably a big win. If only they’d had Sackson’s notebooks.

Wreck of the BSM Pandora originally appeared in Ares magazine #2 (May 1980) and subsequently got re-released as an SPI small flatbox, which cost about eight bucks in those days. Ares was a short-lived counterpart to SPI’s flagship magazine, Strategy & Tactics, which was “the magazine with a game in every issue” in the 1970s. Those games were wargames, but with the explosion of fantasy role-playing games around that time, I can only imagine SPI wanted to attract a piece of that market. Ares lasted only 17 issues* (unlike Strategy & Tactics, which passed through the hands of several owners but is still being published, currently on issue #281), and carried a game in every one. Some were good. Most were interesting. Wreck of the Pandora was both.

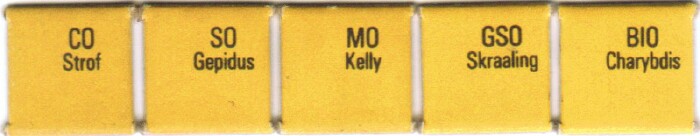

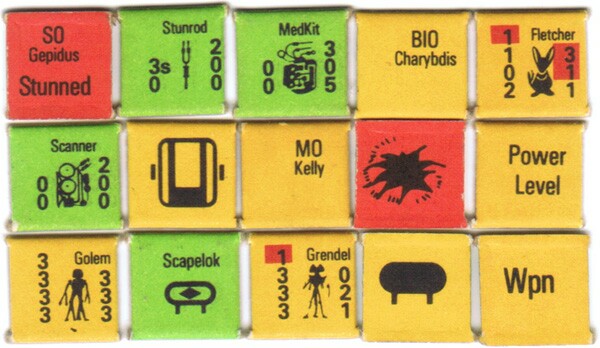

Ares may have been a “magazine of fantasy and science fiction” but SPI was a company of wargaming. The difference between reading a set of SPI rules and those included in most science fiction games at the time was like the difference between reading your attorney’s opinion on how to document your Swiss tax shelter, and reading your hippie neighbor’s instructions for making his favorite pot brownies. Having SPI publish science fiction rules was great for preventing rules arguments. Unfortunately, the wargame approach bled over into other aspects of the game. I can show you exactly what I mean by just showing you the pieces representing the Pandora’s crew members, which are the main actors in the game.

That’s it. I’m not kidding. The rulebook has little paragraph bios of those square chits, which I can’t possibly keep straight because all I see is some text and a lot of yellow. It’s not like they ran out of room, as you can see. GSO stands for “Ground Survey Officer” by the way, if you were wondering. I wasn’t, actually, because I’m already done with them. I was done 30 years ago and they haven’t gotten any better.

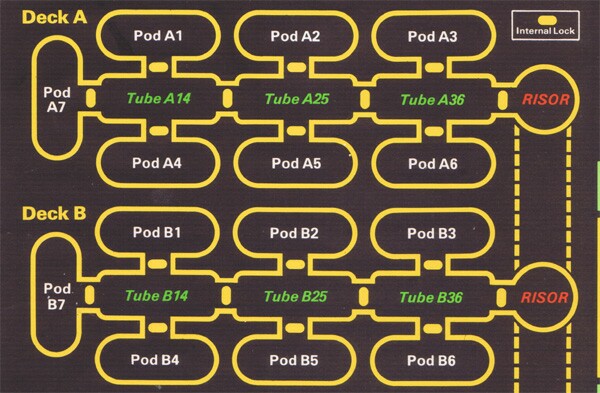

The ship itself is the same way. It looks less like a ship and more like a backgammon board. All the areas are perfectly symmetric. There are hallways, pods, and risors. They all connect in a way that we’ve seen on dozens of “realistic” spaceship models which resemble an erector set painted white. I can almost hear Jim Dunnigan and Redmond Simonsen congratulating themselves on the fact that this well-known model matches the ship drawing on the box cover which matches the deck plan on the map. “Yep, Red, it sure looks historically accurate.”

The late Redmond Simonsen was actually one of the pioneers of his field, responsible for advancing the graphic design of wargames far beyond their primitive origins. He is tremendously respected for it.** Mr. Simonsen unfortunately died prematurely in 2005 and had his obituary printed in the New York Times. Nevertheless, I can’t call Wreck of the Pandora one of his finer moments.***

But that’s all the fun I get to poke at Wreck of the Pandora, at least for a few more paragraphs, because it’s a neat idea and a pretty intriguing design. The idea is that a ship on a biological survey mission gets disabled in space, and you have to save her. The rules explain the situation on the very first page.

As Pandora enters FTL mode, the nearby Wolf-Rayt [sic] star emits a powerful burst of near ultraviolet radiation. Pandora’s computer has placed the ship too close to the pulse and the results are catastrophic. All over the ship, electronic components are burned out. Systems begin to fail, first the primaries, then the backups.

I looked it up, and it’s actually Wolf-Rayet, hence the [sic]. But however you spell it, it definitely spells baaaad news for the crew. Some of the biological specimens have been released from stasis, and the ship is generally a mess.

Those crew members who survive are disoriented, frightened and not totally aware of what is going on. Most short term memory is gone. There is a certain awareness of being aboard ship and even the nature of the ship. Emergency systems are obviously on and, equally obviously, malfunctioning. Specimens can be observed wandering freely about the ship, many of them carrying about and curiously examining portable ship’s tools.

I wonder if Jim Dunnigan had a “eureka” moment when he thought of this, which gives you a historically accurate reason for doing the main thing you do throughout the game, which is to search the ship for its vital control systems. Because otherwise it would just seem a little odd that neither the captain nor any of the crew can remember where, for example, the navigation system is. But everyone is a little dazed and confused, and for that reason you can have 21 pod counters all over on the map, and you are going to have to flip them over one by one until you find the systems that can turn the ship back on.

That wasn’t making fun of the game. It was just a factual assessment. Another factual assessment is that it’s not that simple. Each space on the ship has to be searched. The ship’s controls are all based in pods, which extend symmetrically from the already described symmetrical hallways. It’s like searching a bunch of toilet stalls: you open the door, look inside, and then go back into the hallway. Except the hallways outside the toilet stalls, er — I mean pods — are divided by hatches. So to go from stall to stall you have to go into separate little rooms. They’re like waiting rooms for the next stall, except that there are stalls on both sides. There are three separate hallways, connected by a series of risors. It’s basically a three-level flying restroom.

There’s a good reason for this, which is that you’re playing the system, not the other players. And the whole point of that story you read earlier about temporary amnesia is that no one knows what is where, and the whole point of dividing the ship up into teeny-tiny pieces is that you have to have a justification for randomly drawing new units each time you enter a new space. Just like many bathroom stalls in current times, future bathroom stalls also have spaces underneath the doors that you can use to look in before opening the door. Except in the future they’re called “viewports.” But the time units in the game are so short that you can’t look through the viewport and go into the stall in the same turn. You have to bend way down, check out what’s in there, and then wait until next turn to go in. Or just go barging in without looking. Is that a monster or somebody’s pants? Whoa, better wait until next turn!

And that’s the deal with Wreck of the Pandora. You walk around the ship, flip over counters, and roll to see if there is anything else in the stall you are searching. If you trip over the specimens, which are the “space monsters” you so helpfully collected but now are your biggest obstacle to setting the ship straight, they may attack you. If you look through the viewports first, you may be able to avoid being attacked, but it will take you forever to right the ship. And you don’t have forever. Because the power is running out.

I know I didn’t mention anything yet about the power running out. But it can, and does, through a neat mechanic called Cold Shutdown. If the Power or Envio**** systems are found to be in condition 4 or less (out of a possible 9) at discovery, the race is on. You multiply the condition level by 5 (so max of 20), put a marker on the Cold Shutdown track there, and decrement it one each turn until you either fix the system and successfully reboot it, or the ship shuts down. And you’re dead.

Even if the ship isn’t in cold shutdown when these systems are discovered, it can be triggered by failed attempts to reboot the ship. If a reboot attempt fails, all ship system levels are reduced by two, which can trigger cold shutdown if it takes Power or Envio to 4 or less. So you shouldn’t just go trying to reboot the ship.

Except you will, because while Wreck of the Pandora may seem like a cooperative game, it’s not. Although all the players are trying to save the ship, they get individual victory points for things like killing/restraining specimens and rebooting the ship’s systems. Each player also loses a number of victory points equal to the sum of all his or her attributes, which is an interesting game-balancing mechanism. But the main thing is that it might make sense to wait and repair some systems further before you go for a reboot, or use one of the special consoles (Computers for +1, Navigation for +2) for bonuses to your die roll. Sadly, if you wait for the perfect moment, someone else may do it for you. Better to do it yourself!

That’s the essence of Wreck of the BSM Pandora in 1,500 words. Are you sold? I have to say, I was. It evokes everything about desperate, doomed starships, like the Valley Forge in Silent Running or the USS Cygnus in Black Hole. And just like those movies from 1972 or 1979, you can tell that Wreck of the BSM Pandora is one of their contemporaries, because no way in Hector would someone make a game like this today. At least not this fiddly. For the same reason, it’s adorable, just like those movies. Next time I’ll show you what I mean.

_________________________

*You can download pdf files of the whole Ares print run here.

**Shenandoah Studio’s original name for the company prior to the announcement of their Battle of the Bulge game was “Project Simonsen.”

***I also should acknowledge that the counters for the prequel game Voyage of the BSM Pandora, released less than a year later in Ares #6, showed some improvement in this regard.

****I assume this is short for Environmental, but the fact that it is not “Enviro” drives me crazy.

Discussion

No comments yet.