The other day on “As It Happens,” I heard the head of some Canadian historical society complain about the latest outrage in Canada, which is apparently the impending desecration of some Canadian pioneer cemetery. But here’s the thing: the cemetery in question is already under a parking lot. Regardless, this guy kept going on and on in the same way that one of your D&D friends probably told you it was unfair that you killed his 15th-level fighter with poison because even though he was armor class negative a lot, he wasn’t good at not being killed by poison. This got me to thinking about space strategy games.

Actually, that’s not true, although the guy with the 15th-level fighter did get me wondering: if a cemetery that essentially isn’t there is still a cemetery, what about a game that was missing a bunch of features? Maybe there is no way to get to them while in the game, because all the bits and bytes and computer whatever things were trapped under the giant parking lot of the game interface. For all I know, Panzer General had a bunch of secret vampire units, but only some Canadian historians knew about it.

During the David Stockman administration, SSG released a game called Reach for the Stars. Much like its contemporaries (none) it didn’t really have any plot or story to it, because by law only Zork and Ultima could have those. Even its name – Reach for the Stars – was generic. Master of Orion evokes images of a skilled hunter among the constellations tracking down giant ants who are good at making things, but when you reach for “the stars,” you could be reaching for any star – at least any star that isn’t part of a complex backstory.

About one million years later in computer game time, SSG released a sequel to Reach for the Stars, called Reach for the Stars. There are lots of laws that are only known to people like me who think about computer games far too much. One of these laws is that games from the olden days cannot be as good now as they were back then. There are a lot of complicated reasons for this, one of which is that asterisks are far less representative of stars now than they were when Carl Sagan was alive. At that time, the asterisk was the best possible way you could portray a star system on a computer (narrowly edging out the not-quite-as-starlike letter “X”). Appropriate ways for denoting advances in technology involved Roman numerals, since back then it wasn’t so long ago that we were in Roman times. Thus, the tech known as Missile I was followed by Missile II. There were probably only three Missile techs, total, because by the time you counted the asterisks, the techs, and the screen with the credits on it, you had pretty much filled up your 16K of memory. Needless to say, a backstory was an unimaginable luxury that probably got printed as an afterthought in an issue of Vanity Fair, to which you could subscribe if you called the number on the screen when you beat the game on the hardest level. Since you had to finish the game to find this out, the backstory really didn’t have much to do with playing.

That all changed when computers got CD-ROM drives and full-motion video. All of a sudden, backstories became indispensable. Some even developed lives of their own and became full-fledged games, or even short novels and the resulting TV series. But behind all the inflated egos and contract disputes and writers’ strikes, these stories were serving an important purpose: they were allowing games to become more complex.

Lots of gamers completely missed this point, choosing instead to take the stories at face value as art, and to favorably compare the story in one role-playing game about being dead to the one in another role-playing game about killing orcs. You know what? You or I or anyone reading this could walk to his bookshelf right now, pick up anything by Flannery O’Connor, and immediately have a story that is more than one billion times better than the best computer game story times one zillion other stories. So obviously the stories themselves aren’t what’s important – it’s what they do. Or what they don’t do, if – like the designers of Reach for the Stars – you forget to put one in that makes any sense.

When Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri came out, a lot of people went completely out of their minds about how wonderful the “story” was. In case you missed it, here’s that story in its entirety: seven racially diverse caricatures of modern-day Earth ideologies as seen in Mother Jones crash-land on an alien planet. And they fight. The end. Booker Prize?

Before you send me some crazy email about how there’s so much more to it than that, and that the Gaians are really a sophisticated commentary on the Bush Administration’s decision to back out of the Kyoto agreement, let me explain something: you may very well believe that’s the case. Even famous game designers and writers of end-of-manual designers’ notes like Tim Train may believe this. There may even be people who think that some kind of novelistic exposition of the events in the game is crucial to the gameplay. But it’s not. While some people may write scary mash notes to the (very) fictional faction personalities, that’s a pre-existing illness and not a result of the game design. The story serves one purpose and one purpose only: to put things in a familiar context. So that you can remember them.

Here is a quiz for you. Below is a paragraph from the Reach for the Stars manual.

The Arimechs are highly intelligent creatures possessing only crude tentacles with which to manipulate their environment. By trading ideas with other species they have acquired the necessary technology to conquer their surroundings and venture into space. Almost never seen outside a protective exoskeleton, the Arimechs can live almost anywhere, simply creating the appropriate travel suit for any environment. Everything about Arimechs is flexible: ship design, technology, and diplomacy. They are the greatest traders in the galaxy. They prefer peace but understand war and have no qualms about prosecuting it vigorously.

Without looking back at the text, what do the Arimechs use to grab onto things? I had to first read that paragraph and then type it in and then check to make sure I didn’t screw it up when I typed it, and I don’t remember, either. That’s ok, though, because it’s completely irrelevant. Here is something that is not irrelevant: in Master of Orion, the Klackons are big ants. Why? Because ants are good workers, and Klackons get production bonuses. Notice how I remember that, yet I didn’t just type in a big paragraph about it.

I saw Wall Street way back when it was in theaters, so I’ve had over a decade to assimilate the now well-known axiom that greed is good. Therefore, when somebody presents me with a well-dressed man by the name of “Morgan” and informs me that he’s very rich, I can pretty much write my own backstory right there. This backstory then serves as a mnemonic device to make sense out of all the subsequent arbitrary game devices that Reach for the Stars has somehow transformed into Arimech tentacles. I know a planned economy is bad because it’s not much of a leap from Hitler or Milosevic to rounding people up and dumping them in mass graves, so when I need to choose an economy for J.P. Morgan’s team, I know right away that “planned” probably wouldn’t work. For role-playing reasons. And guess what? It’s prohibited by the game rules! I could probably sit down right now with only the Critique of Pure Reason and the dungeon master’s guide from some space role-playing game and figure out the rest of the game’s rules just from the leader portraits. By way of contrast, just now I read the planet suitability characteristics for one of the space races in Reach for the Stars, and not only can I not remember what they were, but I’ve already forgotten what the name of the race was.

I’m involved in a PBEM game of Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri with a few of the people who read this site instead of working at their jobs as game writers. We heard this Sid Meier guy was famous, and then one of us was like, “Damn, maybe I should check out one of his games” and then the rest of us got nervous and asked if we could join in the checking-out process so that no one got an unfair advantage for the next article one of us wrote for CNN about how this whole “computer gaming” thing was really this close to becoming mainstream. So we decided to all play at once. Together. Anyway, I took a few minutes in lab and temporarily reprogrammed some of the incredibly complex equipment we use to torture animals for no reason that I could explain to you right now and have you understand. Basically, I just devised a few algorithms, ran some tests, and analyzed every possible position that could exist in any Alpha Centauri game up to the game-year 2355. (It’s hard to go beyond that for hexadecimal reasons.) A lot of these writer types, though, aren’t so good at math – it’s why they became writers, y’know? Anyway, in terms of the actual game they don’t stand a chance, but this is irrelevant because with a game like Alpha Centauri, it’s not really about who wins – it’s about the deep and complex backstory, in which a group of characters who mysteriously happen to be ideological archetypes battle for control of an alien planet. It’s a way in which computer games make a significant contribution to political discourse: all you have to do is play the game for a while, write down what happens, explain how it’s all the Morganites’ fault, and send the resulting article to The Nation. So these other guys can still get some meaningful work done and not worry about losing. It’s a win-win situation for all concerned.

In Reach for the Stars, though, they’re toast. There actually is a long and complex backstory, but it got overwritten when they burned the actual game to the CD, so there’s really no way to access it while you’re playing. There’s no way to access it while you’re not playing, either, so in many ways it’s like a lot of cemeteries that you might find in Canada. That means that instead of having your misunderstanding of current events help you make sense of the game, you have to fall back on your ability to associate abstract concepts with mathematical relationships. Which formation works better against echelon: line or vanguard? But here’s the tricky part – which works better in space? I don’t think it’ll come as a surprise to many of you to learn that the answer is DGº = -RT ln k. That’s another way of saying it depends on which elf it is.

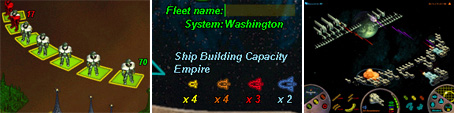

After all that, it will probably come as a shock to learn that the actual game mechanics of Reach for the Stars are far better designed that those in Alpha Centauri. In Alpha Centauri, you eventually have so many units and possible uses for them that successfully finishing the game is sometimes used as a clinical test for autism. Reach for the Stars, on the other hand, has a limited number of planet facilities, technologies, and things to do with them. The problem is that when you scale up a game like the original Reach for the Stars, you eventually cross the threshold between games that can essentially be represented by a single screen of data and thus don’t make you remember anything except that an asterisk looks more like a star than an X does, and games that have Arimech tentacles and as a result make you have to remember basically everything. Alpha Centauri made its equivalent of Arimech tentacles stuff that everyone knows intuitively, like that the U.N. can’t do anything right and that Sparta was the ancient land of Pericles. In Reach for the Stars, I can’t even see enemy fleets in transit, so if an opposing armada suddenly leaves its base planet, I have to actually write down what turn that was and then calculate all the possible places it could be in, say, three turns. If your game requires me to take notes while playing, you’ve failed in your attempt to make a computer game and have accidentally created homework. Since I can get homework for free, I’m statistically not all that likely to buy it in a box for $40. Likewise, if I have to use the tool-tips to remind me which picture of a spaceship is a battleship and which one is a troop transport, you’ve failed. Game over. And I don’t mean that as some kind of gamer trying to be hip by using cliché phrases from twenty years ago to up his street cred. I just mean it literally.

When games had a playing field that could fit on a single screen, and your fleets were just numbers that moved from one capital letter to another, you were essentially just playing space chess. If you take the space chess but make the board ten times larger and throw in a lot more techs and environments and invisible fleets but don’t include any way to keep track of it, you have Reach for the Stars. It’s a shame, because parts of the game are just brilliant. But without a familiar scapegoat, The Nation isn’t going to take your Reach for the Stars article. Which means you won’t get paid. And since a man’s gotta eat, that pretty much seals it right there.

Discussion

No comments yet.