Technology has a way of fixing problems. In gaming, it created distribution models that freed many designers from the restrictive grasp of publishers (direct download), produced handheld devices that gave simple mechanics a chance to shine (iPad), and connected consumers with creators in a way that removed restrictions on capital flow (Kickstarter). But in boardgaming, it left one decidedly low-tech yet-unsolved problem: how do you make games out of various pieces of cardboard without having to farm it out to an overseas printer?

That’s a problem the desktop publishing hobby (movement? cause?) has tried to fix. Troy and I spoke at length with Paul Rohrbaugh of High Flying Dice Games, who has done a great job bringing little-known historical subjects to gaming with little more than Photoshop and his local printer. Paul and others have shown that design skills are out there. The modding efforts of Ed “Volcano” Williams to redo the Panzer Campaign series graphics, or Jison’s MapMod project for the same series or his astonishing efforts in re-imagining the War in the East map, are plenty of evidence that graphics design talent exists as well. But there’s still this seemingly insurmountable problem of taking that design, and the beautiful map, mounting it, and providing good die-cut counters so you feel like you’re playing a real boardgame.

If you were hoping for a link to some amazing deal of a laser die cutter than fits in your pocket, I’m afraid I have to disappoint you. But even if I did, what would that mean? You have to make the game yourself before you played it. What a pain in the ass.

But if you think about it, you’ve already had some experience with this, because there must have been a time in grade school when a teacher told you to cut out some colored construction paper with scissors and glue it to a piece of cardboard to make a Christmas ornament to take home. What if instead he or she had asked you to cut out some colored construction paper with scissors and glue it to a piece of cardboard to make a game that explored the futility of America’s catastrophic involvement in Vietnam? I know, right? Take that, educators!

You can essentially do exactly what I just described by going to Greg Moore’s site, Wargamedownloads. One step below High Flying Dice’s desktop publishing model, wargamedownloads offers “print-n-play” games from a whole host of different designers, for anyone with a color printer, some scissors, and a glue stick. They run usually from three to five bucks, although some of them get to the double digits. It’s a trivial amount of money from an objective standpoint, although it seems odd when compared to a fully functional iPad game that costs 99 cents.

But just like grognards everywhere insist that graphics aren’t everything, there are some pretty neat design ideas just waiting for you to check them out in pdf form. Two gems I found there are both designed by a guy named Dave Kershaw*, and both happen to be solitaire games: ACW Solitaire about the American Civil War, and Vietnam Solitaire about you know what. The way the rules are written, you can start playing both within five minutes of making them.

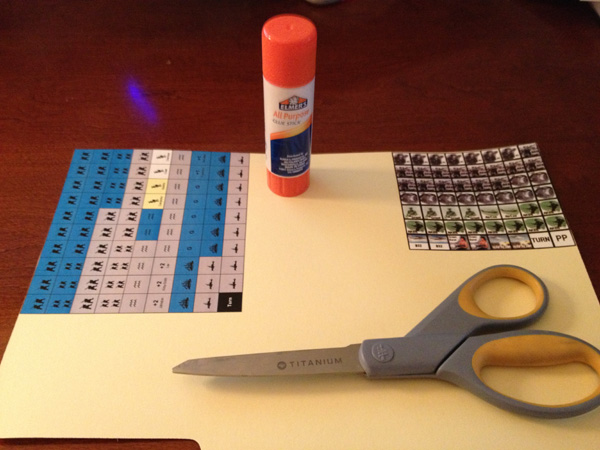

But yeah, you gotta print them out and then at least mount the counters. I used a basic Elmer’s glue stick and a manila folder. And scissors. Please see below:

Then just place the whole thing for a while under something heavy that you are not using. In my case it was a Warhammer Online Collector’s Edition. Sick burn! On me!

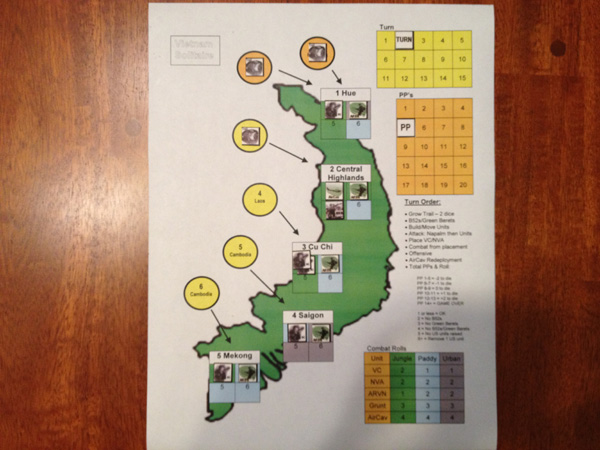

Of the two, Vietnam Solitaire ($4) is more stylized and clever. The game divides South Vietnam into five zones with six corresponding boxes of the Ho Chi Minh Trail (“The Trail” in the game). Each zone is divided into four boxes which have different terrain and correspond to various numbers on a six-sided die. Lower-numbered boxes generally have jungle terrain (advantageous to the North Vietnamese) while higher-numbered boxes have terrain more advantageous to you. Turns start out with the North developing the Trail by placing Trail counters. Each Trail box with a Trail counter feeds North Vietnamese Army (NVA) troops into the corresponding region of South Vietnam. Vietcong (VC) forces also appear randomly in the South. As the U.S. player, you need to prevent South Vietnamese regions from being occupied solely by North Vietnamese troops. Each region so occupied costs you Political Points. Lose a certain number of Political Points and you lose the game.

But fighting the North Vietnamese costs Political Points as well. You can bomb the Trail to keep those markers from spawning troops. Costs points. You can deploy South Vietnamese and American troops to eliminate the enemy ground forces. Costs points. You can use napalm to attack targets you can’t reach by ground. Costs points. In fact, doing pretty much anything in the whole game costs points. But you just have to spend money to make money, right? Eventually you save the day? Free Republic of Viet Nam?

Not really. Kershaw has a half-page of notes at the end, making it clear that he felt that the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam was inevitable due to the political cost. The whole game flows from this. There is, in fact, no victory condition for the player to meet. He or she will always “lose.” The Political Point track ends the game when it reaches 14 at the end of a turn, and the game is designed so that it will get there eventually. You can’t prevent the fall of South Vietnam, period. All that’s left is to see how long you’ll last. If you make it past the historical 1975 end date, you win. I guess.

But just as you know you’ll die eventually in a roguelike but you play anyway, Vietnam Solitaire has a draw to it, urging you to see how long you can play before the civilian helicopter evacuation. As I was playing through the game, it struck me again how this is a clear solution to the “this AI sucks” problem in single-player games, which are essentially computer solitaire games. The best example of this is Dan Verssen’s Phantom Leader, which also has an iPad implementation. Vietnam Solitaire would probably make an interesting iPad game if you presented it right. Most if not all of its design success could be translated to a digital format. The principles are all sound.

I think my favorite thing about Vietnam Solitaire is how clean the design is while still solving the problems inherent in a Vietnam scenario. The regions with subdivided terrain boxes are a brilliant solution to the problem of presenting heterogeneous terrain in a single area. Your troops retreat from combat to a higher-numbered box, meaning you’ll eventually get to advantageous terrain but at the expense of abandoning the countryside. Having five geographical regions and six Trail boxes allows you to govern everything with a six-sided die. Each turn (year) the enemy goes on the offensive in one area, corresponding to the die roll. Roll a six, and you have a countrywide offensive like Tet.

It seems to me that the best strategy for the game may be to not commit any U.S. forces at all. While that’s consistent with the game’s larger premise and an interesting twist on a Vietnam wargame, if true it means that the only way to fight the game is to let it fight itself. I don’t know if this bears out, but that possibility shows what can happen if you bend a game system too far in one direction.

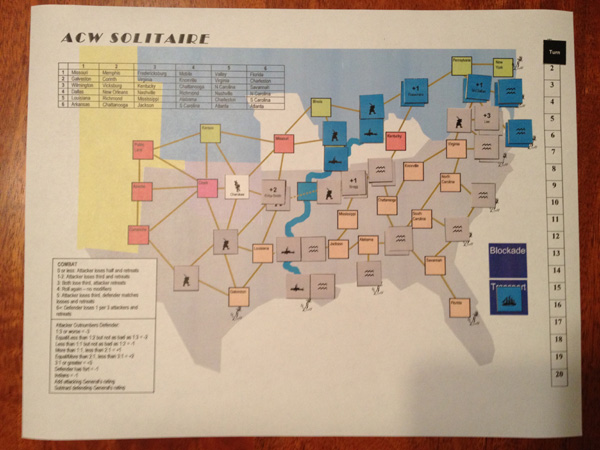

Kershaw’s ACW Solitaire ($5) moves away from this model by introducing your opponent as a similar side (the Confederacy vs. your Union) playing by the same rules that you do. Unlike in Vietnam, you’ll eventually win. But take too long and you lose. In the process, you need to remotely control the armies of the secessionists. While the systems differ, it’s clearly the work of the same designer.

Design principles that served Kershaw well in Vietnam (2006) re-appear in ACW (2007). The South gets up to four build points per turn, one for controlling Atlanta or Richmond, one for not having the Mississippi closed (basically a point for Vicksburg or New Orleans), and two relating to blockade and control of ports. Each turn the Union futzes around, the South builds more stuff. This gives the Union clear objectives to chase in order to shut down Confederate production, just like the U.S. had clear targets in Vietnam. The difference is that the Union gets five build points itself, so that just like South Vietnam in the previous game, South America can’t hold out forever.

But as you move armies from box to box, so does the Confederate enemy. Decisions are driven by die roll and then simple priority, giving an acceptable mix of randomness and direction. But in ACW, when the system leads to what is objectively a “bad” move, you curse the flawed system. And then when it pulls a sneaky trick and makes a great move you didn’t expect, you … no, of course you don’t applaud the AI. You can see exactly how it came to that decision, and it wasn’t some sort of sneaky genius.

I wonder how often we’re hoodwinked by exactly this kind of random move in games where we don’t have the luxury of seeing how the AI arrives at its decisions. I wrote a while back how you can’t bluff a computer, and what happens when you do anyway, but I’ve seen plenty of “good moves” by machines that were probably as accidental as the bad moves that preceded (and succeeded) them. The big downside to a manual AI like this is that your robot is totally naked.

Vietnam Solitaire is a great example of game which use a system skewed against the player to act as an AI. It’s a simple system with clear decisions and immediate results. And the lack of a real AI, manual or otherwise, leaves you reacting to the system without expecting it to make any stellar moves on its own. Your performance is based on how well you react to the forces of nature. Which don’t, by the way, sit around pondering the best way to invade Pennsylvania.

There is a lesson in here for any game designer, and not just those with a penchant for arts and crafts, which is that there’s an alternative to trying to make an AI think like a human player, and that is to make the system structurally superior without making it break any rules the player uses. In an asymmetrical game like Vietnam Solitaire, it uses different rules entirely. As the sides become more symmetrical, the “robot-think” bleeds through, and you end up cursing the AI for playing “dumb.” I think that’s an argument for more asymmetrical games. I like that outcome a lot.

Dave Kershaw actually has two other solitaire offerings: Solitaire Caesar and Barbarossa Solitaire. For a discussion of the latter, I direct you to an excellent playthrough by spelk at sugarfreegamer. For a discussion of the former, maybe you can check it out and let me know. And be sure to trick out your copy, like so.

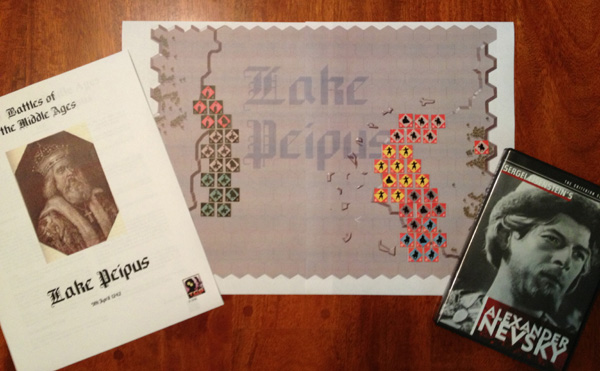

Wargamedownloads has a lot more than solitaire games. There are historical games, fantasy games, even sports games. You can buy a 200+ page treatise on the old Avalon Hill classic Stalingrad, written by an expert player from the olden days. And there are a host of interesting games about obscure topics for the price of a few bucks plus some elbow grease. I grabbed this one about the Battle on Lake Peipus, and it got me to pull out and watch my copy of Alexander Nevsky. Teutonic Knights vs. Novgorod! For five bucks? Please. Get me a fresh glue stick.

*You can hear me talk about Vietnam Solitaire with designer Dave Kershaw on Three Moves Ahead episode #257.

I played Kreshaw’s Solitaire Caesar using a Vassal module, which was a lot easier than building it myself. I’d really like to see more games of this sort using Vassal; the small maps work quite well there.

Posted by Scott Kullberg | May 7, 2014, 12:03 pm