This is Free Trader Beowulf, calling anyone … Mayday, Mayday … we are under attack … main drive is gone … turret number one not responding … Mayday … losing cabin pressure fast … calling anyone … please help … this is Free Trader Beowulf … Mayday …

–cover of the original Traveller game box

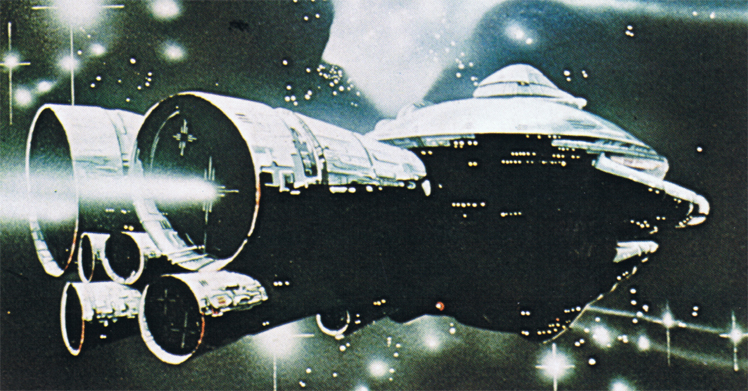

One of my favorite books as a child was this oversize picture book called Space Wars Worlds and Weapons. It’s basically just a big book of paintings of science fiction stuff: aliens, planets, and lots of spaceships. There is some desultory text trying to tie these themes together, but it’s really all about the pictures.

The book starts out with a section on “space vehicles,” and the text quickly bogs down.

However you call it — star ship, rocket ship, space machine — the space ship is the foremost, some would say ultimate, sf symbol. If science fiction is all about other worlds, then the space ship is a part of that other-worldliness, connecting solar systems and universes … the public transportation factor.

Oh dear. I never thought of the spaceship as a futuristic version of the Number Six bus. But the pictures made up for it. Furthermore, they each had captions that were written in a historical style that purported to convey this invented history as fact. The one at the top of this post (illustration by Edward Blair Wilkins) was captioned:

The Starcutter. This was the United Federation World’s most notable post-Interregnum passenger liner. Built at a time when Interworlds Thruspace Co. had captured the bulk of the passenger and mail service between the colony worlds, her design had to fulfill the twin requirements of the 17-day “thru space” interstellar service, and the more relaxed, visually more accommodating long range Einvelocity cruise.

There are also some specifications which describe its “space displacement” at “48 ziemen.” Yeah, it’s silly. But if there wasn’t some part of you that just now started to think about how someone could devise a game mechanic to differentiate between the business aspects of fast space passenger travel versus Einvelocitywhatever in the context of a sweeping game about interstellar travel and commerce measured in ziemen, then I’m not sure why you’re reading this website.

The reason I can quote all that to you now is that that last year I ran across it in a used bookstore, minus its dust jacket, and purchased it using a freshly laundered five-dollar bill I had found in my jeans pocket that morning. When I got home, I immediately remembered why it had fascinated me so much all those decades ago. Because there’s nothing quite as effective at reconnecting with your former eight-year-old self as a beloved, familiar picture of a cool spaceship.

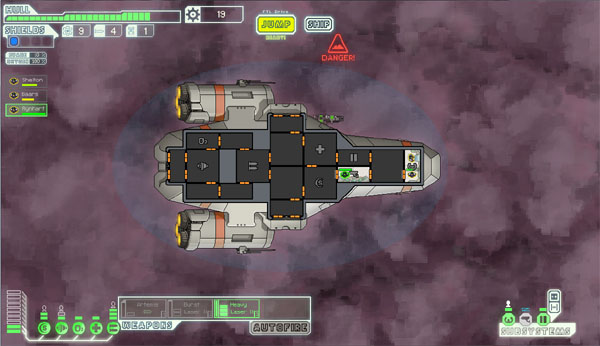

Right around the time of that serendipitous library addition, I stumbled upon another spaceship-related spending opportunity. This one was slightly more expensive, but for a very reasonable price I was able once again satisfy my inner eight-year-old and support a couple of aspiring game developers by backing the Kickstarter for a game called FTL, about a spaceship on a mission to wherever, chased by the rebel fleet. Along the way, you fight, and fight. And fight and fight and fight. It’s really a roguelike in which you need to salvage scrap, and then upgrade this, and buy that.

All very reasonable, and a great idea to anchor a design. But I have to say, I got hooked on another part of the game entirely.

I liked the crewing.

You know what I mean: people doing stuff on a spaceship. FTL puts you in command of a spaceship as well as the little crewmembers who move back and forth in real time, manning the weapons, getting a few more ziemens out of the warp drive, repairing the hull breaches and fighting fires.

I am by no means an expert on science fiction, but I do know that there are a lot of shows, serials, and movies set on spaceships. I even like some of them. Blake’s 7 is a narratively strong series about a group of renegades who commandeer a ship, and this narrative makes up to some degree for its horrendous technical shortcomings. I recently discovered Joss Whedon’s Serenity, which has different kinds of problems but still manages to sharply delineate the roles and responsibilities of different people with different skills on a spacefaring vessel. My favorite four-fifths of a movie, Sunshine, is a brilliant exploration of the consequences of critical personal failure with high stakes among a group of close colleagues. At least, it is until it goes completely off the rails a la Event Horizon. And because of these articles, I recently went back and watched the 1979 “classic” Black Hole, in which Maximillian Schell plays a futuristic Captain Nemo, obsessed with a force infinitely more powerful than the forces of terrestrial imperialism. How powerful would it be to render this dynamic in a game?

When it comes to crewing spaceships, it doesn’t get much better than Stanisław Lem’s collection of short stories, Tales of Pirx the Pilot. The very first story, entitled “The Test,” describes Pirx as a cadet at the space academy, as he prepares for a flight meant to test his pilot skills. Bullpen, his instructor, quizzes him in class.

“Cadet Pirx, what would you do if you were on patrol and encountered a ship from an alien planet?”

Pirx opened his mouth wide, as if the answer were there and all he had to do was force it out. He looked like the last person on Earth who knew what to do when meeting up with a vessel from an alien planet.

“I would maneuver closer,” he answered, his voice muted and strangely hoarse.

The class froze in welcome anticipation of some comic relief.

“Very good,” Bullpen said in a fatherly sort of way. “Then what would you do?”

“I would stop,” Pirx blurted out, sensing that he was drifting off into realms that lay vastly beyond his competence. Furiously he racked his empty brains in search of the appropriate paragraphs from his Space Manual, but it was as if he had never laid eyes on it. Sheepishly he lowered his gaze, and as he did so, he noticed that Smiga was trying to prompt him — with his lips only. One by one he deciphered Smiga’s words and repeated them out loud, before he had a chance to fully digest them.

“I’d introduce myself.”

A howl went up from the class. Bullpen struggled for a moment; then he, too, exploded with laughter, only to assume a serious expression again.

“Cadet Pirx, you will report to me tomorrow with your navigation book. Cadet Boerst!”

You wouldn’t know it but the time between writing that last sentence and this one was two hours. Because I couldn’t put the book down after finding that passage. I literally cried with joy to remember how the flies got into Pirx’s capsule and what happened to Cadet Boerst.

I almost hesitate to bring Lem into a game discussion, because while I desperately want games to be as powerful as this kind of literature (and don’t kid yourself, that’s what it is), they’re a long way from that in their current form. And for good reason: it’s hard to inject this kind of humor, vulnerability, and examination of the mundane into game mechanics. In fact, it’s hard to take any of the interactions which make the shows I mentioned above memorable and translate them into a strategy game. That’s the realm of role-playing, and Traveller. Or is it?

My experience with FTL is far less literary but just as dramatic as the events of “The Test.”* My favorite game to date was when I got into a fight I shouldn’t have with a rebel ship guarding a space station. We had a good reason to be there — the station had some scrap for us and we desperately needed to upgrade our power plant to be able to power our latest weapon, a sweet heavy laser. But the rebels beat us up good, and breached our hull just aft of the cockpit. They also started a fire in automatic door control, and in the oxygen plant.

But there was another problem: we were in an asteroid field. And while we were trying to fix the ship, asteroids kept damaging it, at one point knocking out the engines. We couldn’t jump out. So while my crew repaired one system, asteroids were damaging another. I had to cycle through crewmembers as they worked their way into hypoxia, then quickly sprinted for the med bay where another crewmember fixed up their health bars.

I could almost hear my crewmembers encouraging each other as they ran to the med bay to heal up: “Hey man, I got this, you go take care of yourself!” And then we were systems status green, we were a go, we had power to the engines, the engines were running wild.

You should have seen how quickly I clicked on the “Jump” button once my drive was repaired and powered up. It was like a femtosecond. At most. And as we (yes, we) jumped out of that system, I was glad my crew had survived, and repaired the ship, and we hadn’t lost anyone. I was proud of them.

If FTL has anything on Stanisław Lem, it’s precisely that sense of uncertain possibility — that the next time you play could be cruelly short, or a roller-coaster journey to success. Along the way, there will be infinitely many stories replayed without the same ending. I’ve read everything Lem has written, some of it multiple times. I know how it ends. But each time I play FTL, I have no idea what’s next.

There are plenty of “let’s play”-type FTL videos on Youtube. Just type “let’s play FTL” into the search engine of your choice. So I won’t go through a game session here, especially since you may see it from me later in another format. Instead, I’d like to spend the next few days discussing a couple of older games of the familiar cardboard type. They both deal with events aboard a starship, they both came out in the same year, and they have very different things to say about what it’s like to be out there, among the stars.

___________________________________

*I strongly encourage you to read this story, and the rest of the book. In Polish it was published as a single volume, but in English it was translated as two volumes, “Tales of Pirx the Pilot.” and “More Tales of Pirx the Pilot.” Louis Iribarne’s translation is excellent.

Discussion

No comments yet.