I tend not to be jealous of people who are good at things that I’m not. I figure that’s just the way it goes. I mean, I’m good at some things, too. However, I make a special exception for artists. I have a great aptitude for thinking of things with none whatsoever for drawing them, so I can only imagine what it would be like to be able to illustrate my own ideas. If I had this and also had game design skills, then I’d be Tom Wham.

Tom Wham is a game designer who worked at TSR in the early days, and designed some of my favorite games from that era. While everyone (and by “everyone” I mean “serious nerds of a certain generation”) remembers him for his games Snit’s Revenge and The Awful Green Things From Outer Space, my favorite Tom Wham game was released as an insert to Dragon Magazine #51 (July 1981) and called Search for the Emperor’s Treasure. I spent so many hours as a 14-year-old playing it late into the night at a friend’s house. Just typing that makes me want to dig it out and play it, then write about it. That would be a weird thing to do for Starship Week, given that it’s a fantasy game about questing and I just rained all over that parade in the very first article.

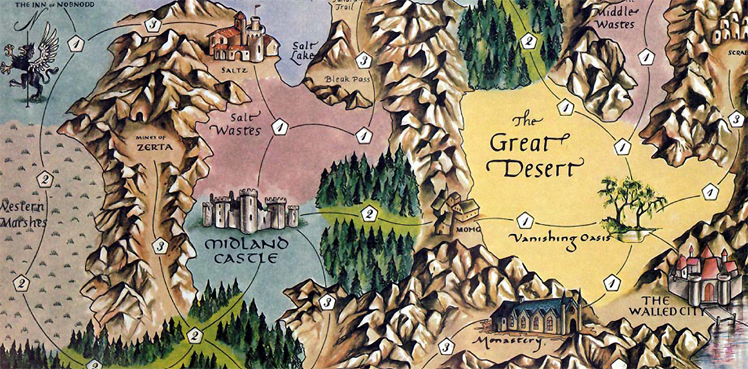

But Search for the Emperor’s Treasure, or SEfT as I have seen it inexplicably be called, is the ne plus ultra of a certain kind of game design: narrative strategy. Narrative strategy games are so compelling in their setting, and so distinctive in their elements, that they can’t help but tell an interesting story every time you play them. It’s like someone made a working world out of a few paragraphs and cardboard squares, and invited you into it to see what happens there. It’s not only a game, its a glimpse into a land so real you wonder what’s going on there when you’re not playing it.

Search for the Emperor’s Treasure is just such a game. It also has one show-stopping bug: there is no incentive for players not to just park their characters on the most advantageous space and then simply draw encounter after encounter. Any worthwhile writeup you’ll find on the web mentions this, and there are different ideas (read: house rules) on how to fix it. Sounds totally broken?

But I’m going to tell you this funny thing which is more scary than funny but also tells you everything you need to know about Tom Wham designs, and that is despite all those many hours we played this game as kids, we never found this rules loophole at all. And the reason for that is obvious if you think about it and that is because what kind of character would just stay in one place and draw encounter after encounter? No character, because it doesn’t make any sense. Fantasy characters have to travel and explore, and defeat the monsters in the Western Marshes and the Great Desert. No one just goes to the Walled City and draws encounters. It’s not historically accurate.

It sounds like maybe we were dumb kids,* but I submit to you that a game which creates such a persuasive milieu that you instinctively play not just by its explicit but also its implicit rules isn’t just a game — it’s a story the game lets you tell, for everyone’s entertainment. Taking advantage of a rules loophole to gain an advantage that clearly isn’t intended doesn’t mean the game is broken — it means you’re broken.

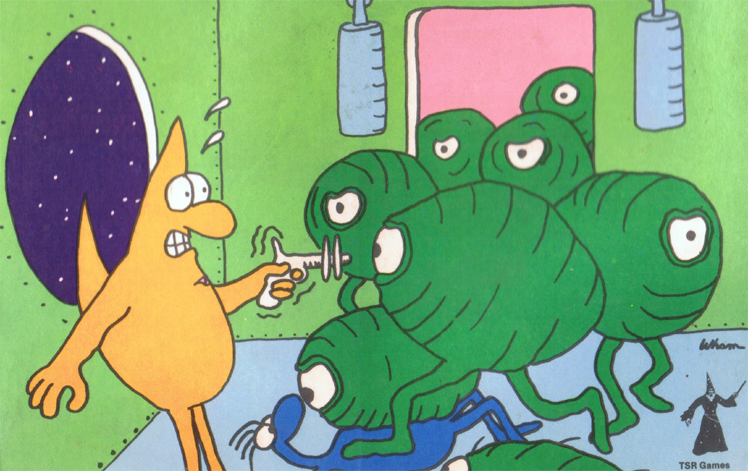

The Awful Green Things From Outer Space is absolutely a narrative strategy game. It’s one of those classic games that every gamer of that certain generation knows. It has been released in multiple formats, first by TSR in the heyday of Dungeons & Dragons, and later by Steve Jackson Games. It calls itself “a preposterous space game for 2 players” on the box, but there is nothing preposterous about awesome.

Awful Green Things does so many things right that it should be some sort of case study in game design school of how to tie absolutely all of your elements together. First, the game comic which starts on the box and continues inside in the rulebook seems like a silly, throwaway story but instead establishes the milieu so well that you feel familiar with the crew before you even set them up. Drawn from five worlds and four races, Wham uses simple differences in appearance and attributes (and his genial, guileless drawings) to establish a clear cast of characters: the pudgy Smbalites, the ostrich-necked Frathms, the tentacled, three-eyed Redundans, and the noble Snudalians, who come from Snudl-1 and Snudl-2 and are presumably recognizable as such by whether they have one or two points on their heads.

Wham takes exactly two 8 1/2 x 11 pages to set this up. There is a robot which is “the miracle of current science.” It has a lot of strength and constitution, so you imagine it may be good at fighting. But it also has fnudding, which needs to be replaced every night with a new batch. Calling this presentation adorable would be condescending. Instead, it’s simply guileless in a way that makes it feel simultaneously earnest, humorous, and adult. The branch of game art that settled for the saccharine, juvenile sentimentality of overdrawn anime chic should have tried this instead before taking over the rest of gamedom. Vulnerability is more endearing when you don’t announce it.

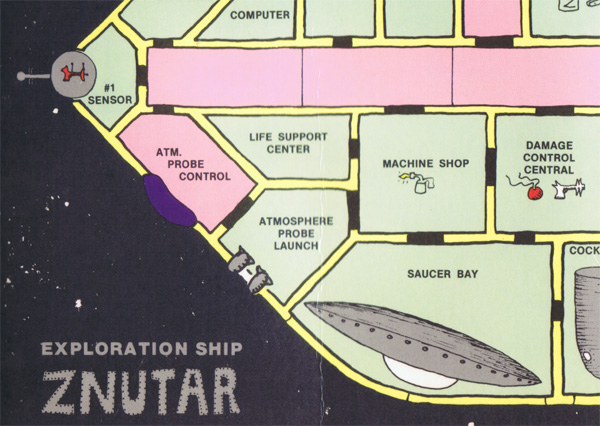

Unlike Pandora’s generic, Lego-pod spaceship, the Znutar is almost a character itself. The pink corridors are a bit hard on the eyes at first, but its layout reveals a geography that makes you note irregularities for gameplay purposes but remember them for their uniqueness. The Captain’s Cabin is right off of Bridge #1. It connects to the Computer Room, but not to the Crew’s Quarters or the Officers’ Quarters. You can run from Bridge #1 through the Officers’ Quarters to the hallway that runs most of the length of the ship, but the other doors lead to completely different places. You can run through the entire bottom of the ship without exiting into a corridors except at the very ends. No way to do that at the top.

These kinds of asymmetric spatial relationships make the process of gaining familiarity a point of endearment. They also have consequences that lend themselves to narrative recounting: I can still remember one game in which Sarge killed the last Green Thing with his back to the wall in the Computer Room, with no way out but a handy fire extinguisher which happened to do five dice to kill.

The game mechanics are your standard circa 1980 hit points, movement points, and dice rolling, with a couple of twists. The Green Things are divided into eggs, babies, and adults, and can also be blown up into fragments. The crew has to stop them before they can multiply and overwhelm the ship.

The big twist, though, is the combat system. Since the Green Things are aliens, it’s not clear how they will react to weapons, or even everyday items. So the first time each item is used on a Green Thing, you randomly draw an effect chit from a cup and that becomes the effect that weapon has each time you use it. There are hand-to-hand weapons like the hypodermic needle and pool stick, ranged weapons like the comm beamer and stun pistol, and area effect weapons like the fire extinguisher. There are also blast-area effect weapons like the gas grenade and can of rocket fuel. The odd assortment of weapons introduces just enough incongruity to make it stand out as a novel game element, and the variable chit draws keep this perpetually fresh. Remember the time the best weapon was the can of Zgwortz? So do I.

This gives the game a lot of replayability while also making it a bit dependent on the results of the chit draw. Most weapons are location-limited, making “grab-anywhere” items such as fire extinguishers more valuable. Having an area-effect weapon do damage makes the crew much more likely to win, while having a good effect restricted to a low-availability hand-to-hand weapon can doom the crew early.

But that’s a lot of the fun of Awful Green Things: the chit draws, and the handfuls of dice, and most importantly the cast of characters established so simply yet brilliantly by the graphic design and that darned comic.

I’m sure I could go on forever about this game, but in the spirit of Starship Week, that’s not as good as playing it. And if you remember what I said at the beginning about Tom Wham designs, it’s designed to entertain you with a story, no matter what happens.

So I’m going to tell you a story about Awful Green Things From Outer Space. It is the absolutely true story of what happened this time I played, making it the very definition of historically accurate. We’re just going to go through the game, talking about it as we play. I’ll show you pictures. My assertion is that if you’re a gamer, even if (especially if) you have never played Awful Green Things, this will hold your attention, regardless of the presence or absence of any scripting or collusion or cleverness on my part. That’s the magic of the game right there. Conversely, if you are a gamer and you don’t enjoy this, then it’s not my fault and something is wrong with you. So it’s not my fault either way.

______________________________

*Being kids did have something to do with it, of course. Narrative strategy games are perfect at that age when you aren’t thinking about your grades, or getting into a good college, or medical school, or have to please your boss, or have a lot of invested money at risk, or need to take care of your wife and children. Heck, you’re not quite worried about girls yet. You can focus all your attention on Ozmo’s quest to the Great Mountains, because, well … that matters.

Discussion

No comments yet.