Everyone knows that strategic games with tactical battle engines are better than strategic games without them. Any game which tries to abstract out combat in the name of tighter, more thematic game design is eventually going to get crushed by complaints from gamers who want to fight out the battles turn by turn, or for truly advanced players, in real time. You know it, I know it, and the American people know it. So why do developers keep missing the boat? It’s so cute that you think I am about to give you the answer. I would never be that straightforward. Maybe I just don’t know.

In a game like Eagle Day or RAF, which is about air combat but really about the cumulative strategic effects of a lot of aggregate air combat, a lot of the specifically individual air combat has to be abstracted out. That’s a shame, because in the end, that’s the most interesting part of the whole thing. Without any prelude, try this excerpt from the Hough and Richards’ book.

McGregor’s Hurricanes were first on the Ventnor scene, as he had predicted, but 152 Squadron’s Spitfires came in seconds later, and a whirling fight ensued before Fisser could get his Ju-88s away. McGregor himself got on the tail of an Me-110, ignoring the rear gunner’s fire, and despatched it with a single burst. Then two more of his squadron began harassing Fisser’s 88 and were joined by two more of 152′s Spitfires. The Kommodore was killed at the controls. The Junkers, trailing flames, dived towards the ground, was pulled up violently, presumably by one of the crew, and headed towards Godshill Park, yawing and only partly under control. It struck the ground heavily, sending up a cloud of pale earth, and slid to a halt, its back broken but the fire self-extinguished.

Pretty exciting, eh? You don’t even have to know who McGregor or Fisser are, or where Ventnor is, or why the Germans were bombing it. You can just picture the wild air melee, with planes diving and rolling and firing, and if you’re a wargamer you’re already trying to figure out how to recreate this for yourself.

But if you spend a lot of time simulating this, you’re going to blur the game’s focus: am I supposed to fight the aerial battles, or plan bombing raids? Paradoxically, the extreme verisimilitude of the aerial combat in Rowan’s Battle of Britain flight sim makes the strategic part of the game seem more real, because you’re not fighting every single battle. But in a strategy game where you end up having to fight every battle, the whole project can founder on tedium as well as impatience: I want to find out how the big battle at Biggin Hill turns out, but first I need to fight these six minor inconclusive dogfights. Or you end up learning how to subvert the tactical system and continually look for unrealistic matchups where you know you would have had no chance historically, but against the game engine, anything goes. The whole thing then seems so much more gamey. There are a lot of admitted drawbacks to tactical battles. But without a good battle hook, where are you? In Eagle Day.

So I gave that away, then. The many fightings in Eagle Day aren’t so compelling. Why?

The two sides in Eagle Day are very different. The RAF player has to react to German raids, constantly evaluating threats and allocating resources. The Luftwaffe player has a much different task, and that’s to plan precise, intricate, coordinated air missions (how German!) and then sit back and watch them happen. I spend a lot of time planning my raids, but once I hit the “start” button, the clock ticks inexorably towards dusk. As the German commander, I can pause it, but I can’t alter it.

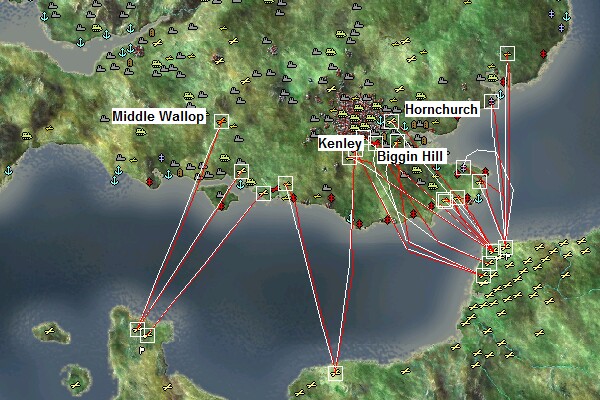

So, fine. Most of the time spent in the Luftwaffe portion of Eagle Day is planning raids. That sounds pretty German to me. Here’s what I came up with for the 13 August “Eagle Day” turn, the historical day of the first all-out attacks on England.

I’m throwing multiple raids at four RAF Sector primary airfields (marked) along with multiple fighter sweeps aimed at secondary airfields where I think I might catch enemy planes on the ground. I can fine-tune every aspect of these missions until it’s time to fly, at which point I can just watch. At that point, the game resolves the day, one minute at a time.

Oh man! Once of my Gruppen is bouncing some enemy fighters. I wonder what will happen!

If you’ve ever played a text adventure, you’ve played Eagle Day, except with gnomes and kobolds instead of Flugzeugfuhrerabzeichen. With each “action pulse”, the aircraft move on the map. If something happens, the game tells you with a text, like this.

You might see a lot of texts. You’re not really sure what went into those text results. Actually, you have no idea. But there they are.

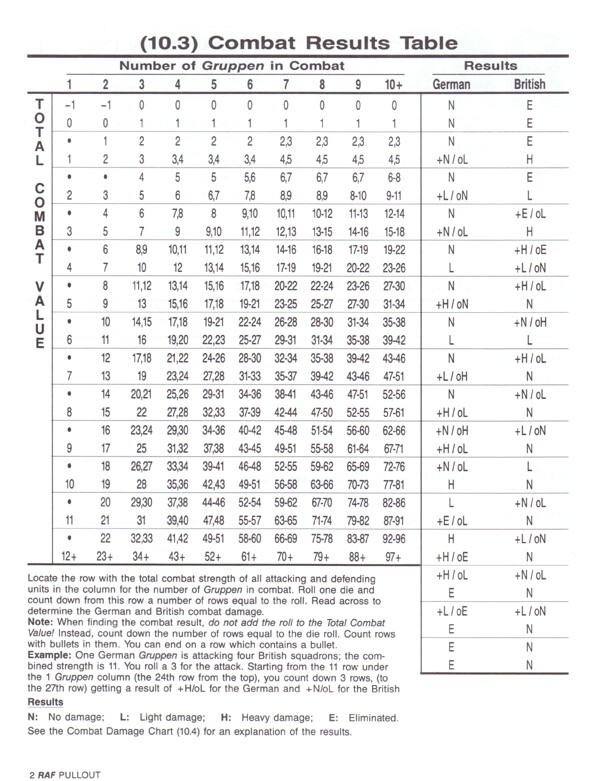

If you’re thinking I’m about to do one of those “check out how this cool boardgame does it differently” things, you’re wrong. RAF has one of the most opaque combat tables ever invented. Just look at it.

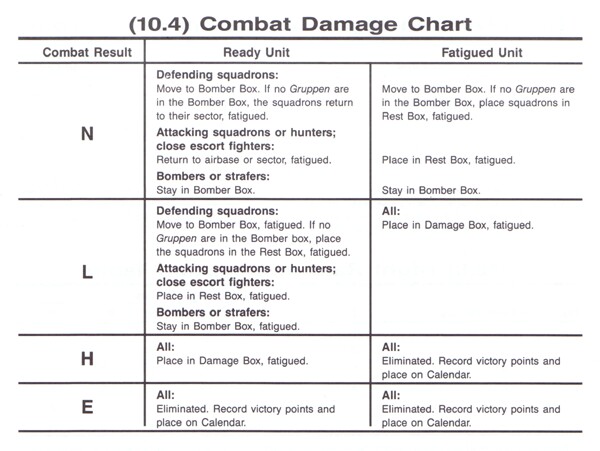

Does that look like it makes any sense? It almost hurts me to have to post it. Don’t get me wrong, it’s actually a mechanistically ingenious way of condensing combat into a single die roll, by trying to account for multiple asymmetrical possibilities in one combat table. The key is the way the game assigns combat strength. German fighters have a low combat strength. British fighters and German bombers have a high combat strength. The key is to have abscissa be determined by the number of Gruppen (German fighter groups) present in combat. If you have a lot of Gruppen but a low combat strength, that must mean the Germans greatly outnumber the British, so the combat results will favor the Germans. If you have a high combat strength but few Gruppen, that must mean either a preponderance of British aircraft, or unescorted German bombers. So the results favor the British. In a solitaire game where you want to minimize the die rolling, it’s a brilliant system.

But the aesthetic result is a blob. What the heck is +H/oL? And all those columns! Such a mess. Let’s resolve that German raid from last time:

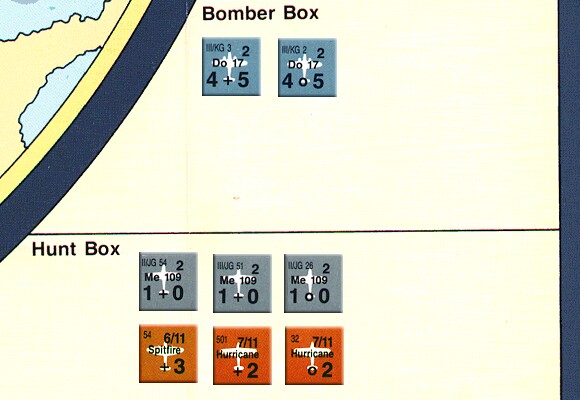

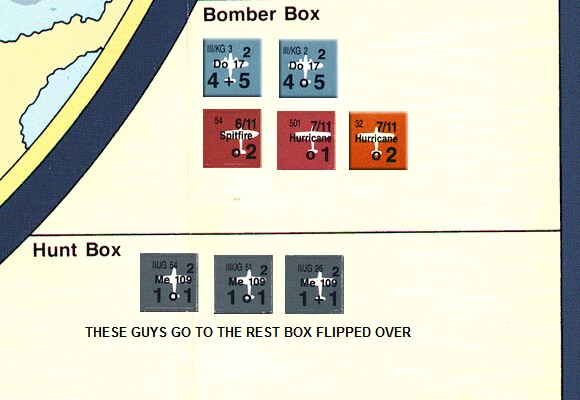

The combat value is the number in the lower right corner of each counter. First, we resolve the Hunt Box. If I’m not turned back, I can get my squadrons into the Bomber Box. So that’s three Gruppen, and a total combat value (TCV) of 7. (The Germans contribute zero, while my Spitfire squadron is 3 and my two Hurricane squadrons are 2 + 2 = 4.) My die roll is a 2. That’s “L” for the Germans, “+L/oN” for the British. All German escorts take light damage, which according to the damage chart, means they are flipped to their “Fatigued” side and placed in the Rest Box. British squadrons with the “+” selector take light damage but can move to the Bomber Box and those with the “o” selector take no damage and also move to the Bomber Box. Two of the British squadrons have the “+” selector. (This is random and built into the design to spread combat results out.) All of my squadrons can now move into the Bomber Box and intercept the Do-17s.

Now we recalculate the combat. The total combat value is now 15, but only two Gruppen are involved (the two bombers). I roll a “4″ which translates into “N” for the Germans and “+N/oL” for the British. Ouch! If you look at the screen below, you’ll see that when my intercepting squadrons became fatigued, their selector changed. So the Germans are unscathed and the British all take light damage. The two Fatigued squadrons go to the Damaged Box. The other squadron goes to the Rest Box, fatigued.

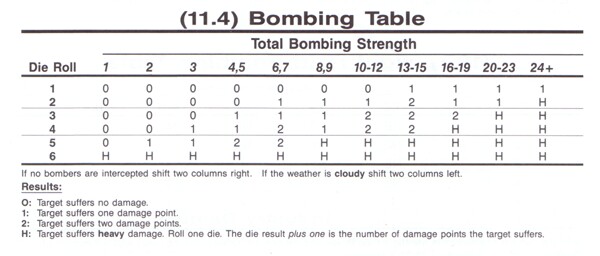

The Germans keep rolling. The total bombing strength is 8. While it’s true the Germans took no damage, they were at least harassed by intercepting fighters, so they don’t get the two-column-shift bonus they would have received if no fighters got through to the Bomber Box. See chart below. I roll a 5.

Ouch again! The result is an “H”, which if you were paying attention last time is -3 victory points.

That’s pretty great, I guess. In Eagle Day, when you bombers arrive over the target, you get a message.

The success or failure of your bombing is supposed to depend on the accuracy of the planes (Stukas dive-bombing are much more accurate than medium bombers at altitude), the bombing skill of the pilots (which increases with each successful mission), and even the reconnaissance level of the target (because you can fly recon missions over a target several days before you attack). Once your planes get back to base, you get an estimated damage level (which simulates the interpretation of gun camera photos). Thereafter, you need to fly recon missions to the target (or attack it again) to stay updated on the damage level. It’s a pretty neat system.

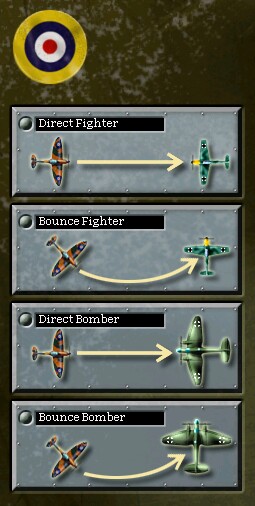

But both air combat systems feel unsatisfying to me. I understand the combined results and random selectors in RAF, because the flow of the game — not individual results — is the real story. But at least I can see what’s happening. In Eagle Day, I don’t even have a good sense for how to improve my performance. Each Gruppe gains experience individually, but I’m not sure what this means or how it helps. Furthermore, there doesn’t seem to be any correlation between the number of aircraft attacking or bouncing and the results. The British actually have a doctrine selector, which allows them to choose the way they attack German aircraft.

There is supposed to be some complex interaction between the type of interception (“bounce” vs. “direct”) and the type of escort being flown. I can not only choose to fly “close escort” with the bombers of “high escort” over them, and I can even determine how much higher the high escorts fly. At some point, I’m sure, the high escort becomes less effective because it loses contact with the bomber stream. Or does it? The game explains none of this. All I have is observational data.

And the thing that this data shows is that I have no idea what is going on. Each time a combat occurs, someone is damaged or destroyed. There is no such thing as a completely ineffective combat. But I don’t see much correlation between numbers of attackers and numbers of casualties.

Which may be intended. Stephen Bungay has a whole chapter on tactics, and in general spends a lot of time trying to explain why the German escort tactics, regardless of method (close escort vs. high escort) were self-defeating. But he also comes up with this fascinating claim.

In war, more is usually better. There are, nevertheless many examples of few beating many. In air fighting numbers count in the long run, especially if the game is one of attrition, but in an actual aerial engagement, they count for less than they do on the ground or sea. A single pilot with the initiative could carry out an ambush and escape before anybody knew he was there. Hard to detect during closing, a small number of attackers engaging a number of defenders could also shoot at almost any target and be confident that it was an enemy. In modern jargon, they were operating in a target-rich environment, and tended to mete out more damage than they suffered. They were only disadvantaged if the enemy was alert and had such numerical ascendancy as to be on the tail of almost every attacker. In general, a single squadron on a single pass could cause more destruction than several squadrons together in a huge melee.

That’s pretty much the opposite of the model used in RAF, where a lot of combat factors lead to a lot of losses. But because I don’t know how the Eagle Day combat model works, I could be totally wrong.

Which brings us to the last quote for today. It’s a pretty long one from Stephen Bungay, from the end of the chapter entitled “Bluffing” which deals with the end of the Battle when the invasion had been canceled and the Germans were just trying to keep up the pressure. Helmut Wick was at the time one of the Luftwaffe’s “superstars” and commander of Jagdgeschwader 2 (JG2), the “Richthofen Gsechwader”. I chose it because 1) it shows that German fighters absolutely could fly more often than Eagle Day allows them to (Wick took off at 1310 on a fighter sweep, landed at 1410, and was airborne again at 1530); 2) it is a perfect lead-in to the next installment, which you’ll understand when it goes up tomorrow, and 3) it’s a compelling story, and games are all about stories.

At 1310 on the afternoon of 28 November 1940, Helmut Wick climbed into the cockpit of his Bf 109 at Querqueville near Cherbourg in Normandy and took off with the Staff Flight on a sweep up to the Isle of Wight. They were accompanied by most of the rest of JG2 and a flight from II./JG77 who were invited to come along to watch the fun. Georg Schirmbock of JG77 was astonished to observe that all of these aircraft were under orders not to make kills themselves, but simply protect the Kommodore as he did so. That morning, the latest edition of the Berliner Illustrierte carried a photograph of a smiling Goring visiting his old unit, the Richthofen Geschwader, with its good-looking new Commander, the direct heir to the position he had once held, laughing next to him. An hour later Wick touched down again, and his ground crew welcomed him as he taxied up, anxious to hear the news. Yes! Another Spitfire, number fifty-five! He was ahead of Molders and level with Galland. Then disaster struck. At 1500, JG2 got a telephone call from JG26 Headquarters to say that Galland had just shot down a Hurricane.

There was still plenty of light. The Bf 109s were quickly re-armed and re-fuelled, and at 1530 Wick led the Stabschwarm back out over his favourite hunting ground over the Needles. Just after he had taken off, a signal arrived at the Geschwader Headquarters. Major Wick was grounded with immediate effect. He was too valuable a personality to be risked in combat.

South-west of the Isle of Wight, Wick and his wingman, Erich Leie, together with two pilots of the second Rotte, Franz Fiby and Rudi Pflanz, spotted some Spitfires climbing to meet them. They were 152 and 609 Squadrons. The Germans dived on them, and Wick hit the Spitfire flown by Paul Baillon who had only just joined 609 Squadron. The plane began to smoke. Wick had to make certain of this one. He fastened on to the crippled Spitfire and gave it another burst. Baillon baled out into the Solent at 1613. Number fifty-six! Helmut Wick was now Germany’s greatest ace! It was a sweet moment.

Hugh Dundas had recovered from the wounds he had received on 22 August. On Friday 29 November he drove to visit his parents. He arrived at tea-time and he was shocked to learn that his father had had a telegram saying that his brother John was missing. ‘Poor Mummy!’ Hugh wrote. ‘If John is killed — and I did my best to persuade her otherwise — I believe that even her brave heart will be broken.’

John never turned up. He lies somewhere out to sea off Bournemouth, as does the 109 he finished, and its pilot, Helmut Wick. Rudi Pflanz saw Wick hit and bale out. Just as the attacking Spitfire turned away, Pflanz managed to get it in his sights and send it into the Channel as well. No trace of either pilot or their planes has ever been found.

Siegfried was slain.

Discussion

No comments yet.