When I was young, I’d read about “playtest sessions” at the major boardgame publishers, like SPI and Avalon Hill. I wished I could participate just once in what seemed like a crazy fantasy. I could just imagine what it was like: a luxurious conference room, with plenty of leather recliners, multiple televisions tuned to the latest news and sports, people doing what they love, chatting about it, and having an endless supply of delicious food and drink continually replenished, as if by magic.

When I was young, I’d read about “playtest sessions” at the major boardgame publishers, like SPI and Avalon Hill. I wished I could participate just once in what seemed like a crazy fantasy. I could just imagine what it was like: a luxurious conference room, with plenty of leather recliners, multiple televisions tuned to the latest news and sports, people doing what they love, chatting about it, and having an endless supply of delicious food and drink continually replenished, as if by magic.

Now that I’m older, I’ve actually been to a place like that, and it’s called a private hospital’s surgeon’s lounge. Still, playtesting a wargame has always been on my list of things to do if I ever got the chance. So after being tremendously impressed with Shenandoah Studios’ Battle of the Bulge, I volunteered to help playtest the other half of the Kickstarter I had paid for, El Alamein. It wasn’t quite what my young self had expected.

The North African campaign has always run a close second to the Eastern Front as my favorite World War II subject. I wrote about the idea of space and possibility in games a while back, and the North African theater fits this imaginative space very well. I recently read Martin Kitchen’s historical study Rommel’s War, one of the few English-language monographs to examine the entire Mediterranean theater from the point of view of the Axis, and was struck by just how remote the theater felt.

There was nothing at El Alamein but a miniscule railway station with a single track, 3 kilometers from the sea, hundreds from anywhere. The road from Alexandria to Sollum is built along an embankment to the north of the station, beyond which are the salt flats and lagoons that make up the coastal strip. The Qattara Depression to the south, which runs for 300 kilometers, is 134 metres below sea level. With its salt marshes and quicksands it is almost impassable, even for loaded camels. For one hundred of these kilometres the Depression is between 60 and 100 kilometres from the sea, and these narrows form the only route to the Nile Delta.

That geographic explanation doesn’t quite convey the feeling.

It was a wretched place. With the exception of Alam Halfa, which was 132 metres above sea level, the ridges that were so important for the defence were so low as to be virtually indescribable. The Miteiriya Ridge was only 31 metres above sea level, that at Ruweisat 66 metres. They were made of limestone so that it was exceedingly difficult to dig in. In addition to the characteristic extremes of blisteringly hot days and freezing nights, over and above the persistent pangs of thirst that made desert warfare so hard to bear, there was the added torture of swarms of persistent flies that came from the Nile delta. Stripped of layers of glamour and myth, El Alamein was one of the most frightful battlefields of the entire war.

The corollary to that bleak description is that the Battle of El Alamein was never about El Alamein. It was just a place on the way to Alexandria and Cairo that happened to pass between the sea and some impassable marshes and quicksands. The battle was fought there because it had to be.

So any game about El Alamein needs to convey the feeling that the battle is really about objectives off the mapboard.

That will be important later.

Rather than flying to Philadelphia on the Shenandoah Studio Gulfstream and being sequestered in a well-appointed playtest facility, my welcome to the playtest consisted of access to Shenandoah’s playtest project which they were managing in part with Basecamp, the collaboration management software from 37Signals. Once there, I found a post with a Word document containing the rules draft, and a pdf file of the map and counters. And instructions to start playing.

El Alamein is yet another example of Shenandoah’s ability to get elite game designers to create their games. Battle of the Bulge was designed by John Butterfield, creator of such classics as R.A.F. and Ambush!, and Ted Raicer, creator of the seminal Paths of Glory, was responsible for Drive on Moscow. El Alamein is the creation of Mark Herman. To enumerate Mark’s full wargaming resume and influence on the hobby would require a separate article, so let it suffice to say that the meeting of Mark’s design talent and Shenandoah’s presentation skills is a high-level conference indeed. Yet with all that, a game on this subject has some unique obstacles to overcome.

El Alamein is yet another example of Shenandoah’s ability to get elite game designers to create their games. Battle of the Bulge was designed by John Butterfield, creator of such classics as R.A.F. and Ambush!, and Ted Raicer, creator of the seminal Paths of Glory, was responsible for Drive on Moscow. El Alamein is the creation of Mark Herman. To enumerate Mark’s full wargaming resume and influence on the hobby would require a separate article, so let it suffice to say that the meeting of Mark’s design talent and Shenandoah’s presentation skills is a high-level conference indeed. Yet with all that, a game on this subject has some unique obstacles to overcome.

Wargames are best when they evoke history, rather than simply being cardboard exercises in factor-counting. Matching your mechanics to reflect the flow of the campaign is what makes the game feel like you’re actually “touching history.” Battle of the Bulge and Drive on Moscow are both about far-reaching armored breakthroughs, and rolling handfuls of dice as massed panzers demolish lone defending units and exploit their successes via the road network feels very appropriate.

El Alamein is a very different situation. The Germans were never able to break through the Allied lines, but the Allied counterattack didn’t materialize until Monty was sure (some would say too sure) that it would succeed. That was four months after the Germans first attacked. In the meantime, the Germans carried out two separate offensives, as well as extensive minefield placement. So your design problem becomes using a system designed for massive breakthroughs for a game four times as long (in real time) and sixteen times smaller (in geographical area) than Drive on Moscow.*

There were actually three major battles at El Alamein: what is sometimes called First Alamein or The Battle of Ruweisat Ridge was Rommel’s desperate attempt starting on 1 July 1942 to push the Allies out of their hastily prepared position near a railway station between a town called El Alamein and the middle of nowhere. The second Axis offensive, called the Battle of Alam Halfa, was Rommel’s last gasp at the end of August (two months later) to force his way past the Allies before his time ran out. The Allied counteroffensive known as Second Alamein didn’t start until late October and lasted through the middle of November before the Axis line finally broke. All together, this “battle” was really many battles on the same battlefield, and lasted almost five months.

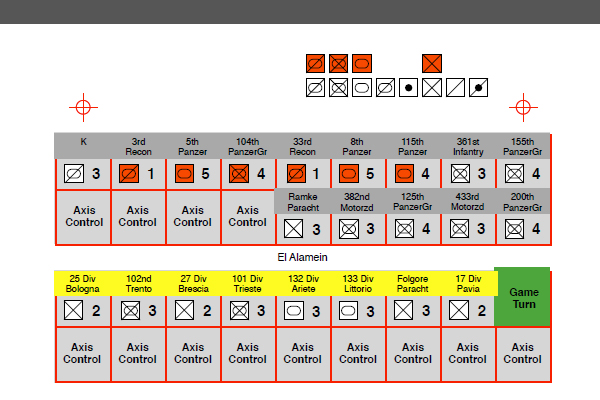

But the first iteration of the game didn’t even cover the entire campaign. Instead, there were three scenarios: two covering the German offensives, and one dealing with Monty’s final attack (Second Alamein). Shenandoah’s instructions were to concentrate on the Second Alamein scenario, which at this point seemed like the showpiece, but it was 14 days long and probably more gametime than I could muster face to face. Luckily, a very close friend (and wargamer) was visiting for the weekend, and I was able to convince him to play the four-day Ruweisat Ridge scenario with me, depicting the beginning of the battle on 1 July 1942.

The first thing we noticed was that while the Axis got victory points for exiting units off the east edge of the map, that wasn’t going to happen unless the Allied player made some huge mistakes. So the game turned into a battle for some spaces in the middle of the map, as well as unit elimination and general infliction of casualties. There were appropriate rules for terrain such as ridges and deirs (depressions), unique to the desert. There were also rules for minefields and “boxes.” The last item was a tactical innovation unique to the desert. Correlli Barnett’s superlative The Desert Generals** has a nice description of this “innovation.”

The basic problem of defense in the desert was the lack of natural obstacles. This meant that extensive use of mines was the only solution. The 8th Army established “boxes” along the Gazala Line. These were forts without walls, sizeable square positions covering several square kilometres, surrounded by minefields and barbed wire, the artillery able to fire in any direction, including the new six-pounder anti-tank gun, which was at least as effective as the German 5cm Pak 38. These boxes were further strengthened by a few tanks, and provided with ample supplies of water, food, and ammunition. The British now had an effective anti-tank weapon in the six-pounder. The ground between the boxes was patrolled by armoured vehicles, with two to three armoured brigades with Grant tanks, ready to meet an enemy attack. The bulk of the British armoured divisions were positioned behind the periphery, with Rommel often uncertain where precisely they were.

The boxes were fine in theory, but of limited value in practice. Once a box came under attack it was virtually impossible to supply and reinforce. The brigades in other boxes were too far away and virtually immobile, so were unable to offer any assistance. The tactic was yet another example of the British frittering away valuable assets in dribs and drabs.

But the rules gave the Axis 3 victory points for eliminating each box, which was much more than they got for wiping out a Commonwealth infantry unit (1 VP) or even armor (2 VP). That seemed odd, given their apparently limited usefulness. On the other hand, El Alamein seemed impregnable, and I never threatened it. The whole scenario turned into a box-hunting exercise. It didn’t seem to really touch any history that I was familiar with.

But that’s the whole point of a playtest: to figure out what is broken. The next time I downloaded the rules, the boxes were gone. And I was greeted by a whole new section, entitled “The Alamein Campaign.” And in that section were rules for upgrades and rebuilds, and some new phase called refit.

This was clearly an ambitious attempt to capture the flow of the entire four-month campaign without sacrificing the existing time clock divided into 30-minute increments. Players would have the opportunity to fight (offensive) or regroup (refit). An offensive would mean playing the game as usual. A refit would allow players to build up their armies but would consume an entire week. Then players could choose again what to do for the next week, and so on.

That captures the rhythm of the actual campaign pretty well. The Germans launched full-fledged offensives on 1 July and 30 August. The British counterattacked in response, but these were local moves and not part of an overall offensive. In between, both sides laid mines and consolidated their defenses. The Allies built up their army and trained new troops in desert warfare. But there wasn’t continuous fighting, and a game about the battle shouldn’t have continuous fighting, either.

The Crisis in Command system can accommodate this well. Each unit has a current strength and a maximum strength, and you can manipulate the balance between present and future strength by allowing players to build up units’ strength and capacity at different rates. So-called “refit points” would give you the ability to slowly expand the number of strength points a unit could have (representing training) while requiring replacement points (actual troops and equipment) to fill them out.

But from a balance perspective, that adds another variable – one with the potential to skew the game hard should one side get on the right side of both the present and future power curves. And that’s something that can only be addressed with rigorous playtesting, where players play again and again, trying different strategies, and the developer and designer address the areas where the game breaks.

The problem was that we were playing the game via VASSAL: a fantastic but time-consuming tool that required a lot of effort to record and play a given turn, and exchanges of turns by email. And the way the game was going, it didn’t seem like it made much sense to play past the second week.

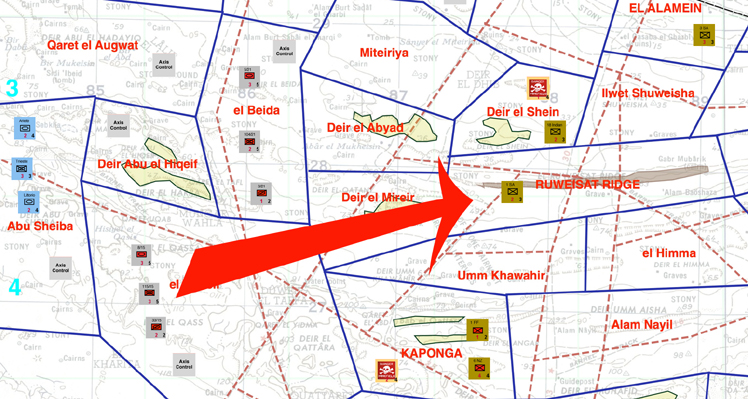

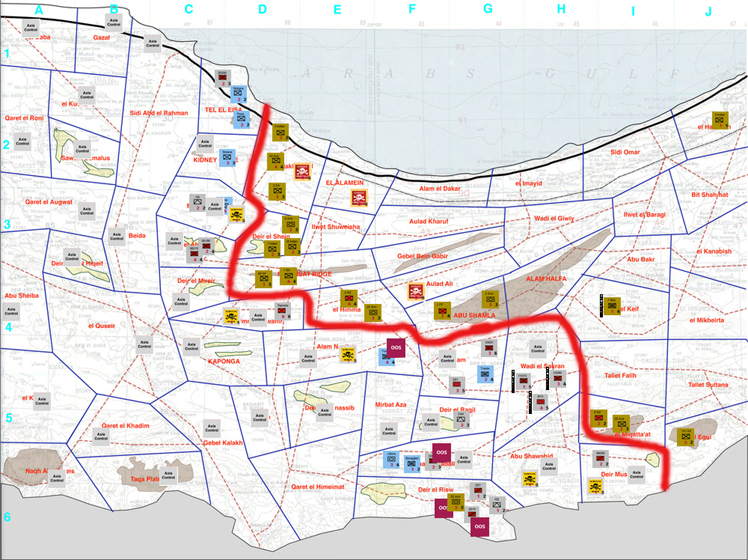

The problem seemed to be the opening position, specifically Ruweisat Ridge. It was the key to unlocking the Commonwealth position in the actual battle, and the Axis never completely captured it. In the game version, if the Axis take it, they can immediately cut the Allied forces in two, and with a little luck can extend to Gebel Bein Gabir, a ridge that runs directly east and serves as an excellent defensive position. With the ridge rules (realistic!) giving defenders on a controlled ridge a 10% bonus, they immediately become defensive bulwarks against counterattack. The ultimate objective is the Alam Halfa ridge, which Rommel was unable to take in the real-life version of this contest. If the Axis get there, the Allies are done. There is no real defensive terrain left, and the Axis just stream off the map and into Cairo.

Furthermore, the Axis chances of taking Ruweisat on the first impulse were good. In fact, they were so good, there really didn’t seem to be much of a point doing anything else on the first turn than attacking it. If the Axis took it, they could slowly leverage the rest of their units forward during the rest of that first week. Then the refit kicked in.

Furthermore, the Axis chances of taking Ruweisat on the first impulse were good. In fact, they were so good, there really didn’t seem to be much of a point doing anything else on the first turn than attacking it. If the Axis took it, they could slowly leverage the rest of their units forward during the rest of that first week. Then the refit kicked in.

At some point in the campaign, the Axis power curve has to peak relative to the Allies (unless you just made it a one-way curve down, which would make the whole “refit phase” kind of pointless). After a bunch of playings, it seemed that this was after about two weeks of refit. With Ruweisat Ridge secure, the refueled and rearmed panzers could drive for Alam Halfa ridge around the game’s fourth week, and the Allies didn’t have enough to stop them. Once the Axis were in Alam Halfa, they could force their way off the map in any number of places. Again, as The Cure would later say: fire in Cairo.

I played a lot of games of El Alamein on VASSAL. I even got into August in a couple of games against Nick Karp, the developer*** (as opposed to the designer), which represents about six weeks (42 days and probably several individual hundred turns) in the game. In one game as the Commonwealth, I managed to hold onto Ruweisat Ridge the whole time, as you can see from the below screenshot. The red line denotes the front. But if you note the southeastern space of Wadi el Sakran, you’ll see three units of the German 15th Panzer Division, free of mines and ready to break out. The line has broken.

We discussed the reasons for this a lot, and while I tended to focus on the initial position, Nick rightly identified the fact that the Germans simply had too much supply.

We discussed the reasons for this a lot, and while I tended to focus on the initial position, Nick rightly identified the fact that the Germans simply had too much supply.

Any game about the North African campaign is going to have to prominently address supply. The Afrika Korps’ supply problems were legendary, and much of Rommel’s energy was spent collecting enough fuel to keep his units mobile. A lot of it is beyond the scope of a game about the battles at El Alamein (although there was an intriguing placeholder in the rules about giving the Germans an option to invade Malta, which would have radically changed the supply balance in the Mediterranean). But the mechanism for supply itself was problematic.

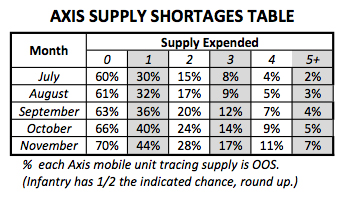

The Crisis in Command system previously penalized out-of-supply units by not allowing them to move or initiate combat. In a game like El Alamein, that seemed harsh and ahistorical, since the mechanism for determining supply state was being able to trace a line of friendly spaces to a map edge, and in the desert, it didn’t seem right to paralyze a unit in this way. So “unsupplied” units had a combat penalty, but could still move one space. This seemed quite satisfying, given that it dramatically limited the capabilities of mechanized units (seems right) while not handicapping leg infantry as much (seems right, too). But the real problem for the Axis was having the supply in the first place. When there is a limited amount of supply even for units able to receive it, how do you decide which units are supplied and which aren’t? Well, it’s a game, so the answer must be … dice.

The initial rules called for a fairly detailed interplay of supply expenditure, unit type, and time period. The Axis player had a pool of supply and received additional points weekly. Each day, he would allocate a certain number of supply points, consult the table (shown below), and roll dice for each unit on the map. Mobile units had twice as much chance of being out of supply as leg units. But because it was a matter of probability, you didn’t have much control. Even with maximum supply, you could still have your key panzer unit rendered out of supply with a bad die roll at a crucial time.

This is a reasonable mechanism for a boardgame, because it introduces uncertainty while still giving you some control over the outcome. Furthermore, it prevents too much analysis paralysis by leaving the results to dice. But on the iPad or PC, this can feel arbitrary. The dice are invisible, and in a game system already susceptible to feelings of being “diced,” this seemed destined to cause frustration.

This is a reasonable mechanism for a boardgame, because it introduces uncertainty while still giving you some control over the outcome. Furthermore, it prevents too much analysis paralysis by leaving the results to dice. But on the iPad or PC, this can feel arbitrary. The dice are invisible, and in a game system already susceptible to feelings of being “diced,” this seemed destined to cause frustration.

During the VASSAL phase, this was modified to include the ability to “protect” one unit per supply point expended. In a world of interlocking consequences, this actually intensified the Axis advantage against Ruweisat Ridge on the first turn, as ensuring supply to your two strongest armor/infantry units gave you a good chance of having a three-unit “maximum attack” as your first move if the other unit in the space passed its supply check. It led to a “Ruweisat Romp” that kept the balance firmly pro-Axis throughout the VASSAL playtest phase.

But when the first iOS prototype rolled around, it introduced a new supply model. Now, you could assign supply from your pool to individual spaces. And instead of a random roll, units expended supply individually, by either moving more than one space, or engaging in combat. Suddenly, the power was all in the player’s hands, with the only limitation being the supply pool.

This change illustrates a key game design fact: no matter how much you imagine a rule’s effect, there is no way to know how it will actually feel in practice. Because while in theory this solves the problem of player agency, in practice it feels somewhat off. Rommel’s supply situation was never this straightforward, and allowing the Axis player to micromanage things to this degree just felt ahistorical.

However, this rule change contained a kernel of genius: having units expend supply individually gave digital Rommels a way of protecting themselves against unexpected supply outages at the expense of unit capability now. Want that panzer available tomorrow? You can’t attack with it today, or move it more than a single space.

This identified the single most frustrating aspect of the old supply rules: you could have a unit be in supply one day and out of supply the next, just because of the dice. Allowing units to preserve supplies from one day to another fixed this, and thus allowed the reintroduction of the old supply model, which showed up one day in a recent build.

The new build introduced some further complexity, with the likelihood of supply being a function not only of how many supply points you expended, but how far a given unit was from a supply source. But in my opinion, the perfect balance had been struck: you were not fully in control of how much supply you got, but you were mostly in control of how much you spent. The uncertainty of the supply situation is prominent in any discussion of the desert war, such as this one by David Fraser in Knight’s Cross, his excellent biography of Rommel:

Replenishment prospects had always swung between grim and uncertain, and had never been far from Rommel’s mind. On the one hand he himself devoted a good deal of time and ink to complaining about the incompetence or worse of the authorities, both German and Italian, who failed to keep his army better provisioned, so that he has been criticized for unconstructive nagging. But the factors controlling supply of an army fighting in North Africa (where virtually every commodity had to be brought by sea), although easy to comprehend, were variables. They could be affected, and win a different significance in the equation, as a result of action taken by one side or the other.

That sounds about right: players can affect supply by spending points, but the result will be variable, and they will likely resort to unconstructive whining about the dice. Feels very historically accurate!

I really liked the inclusion of distance from the supply source in the equation, because in an abstract system I think it’s important to link as many systems as possible to things happening on the actual gameboard. The Allied interdiction system is another example of this.

Historically, the “Desert Air Force” played a key role in interdicting Axis supply and ground movement. The initial system gave the Commonwealth the ability to attempt to put a single space out of supply. Dice were rolled separately for each unit located there, and compared to a fixed value that changed based on date (reflecting increasing Allied and declining Axis airpower). The Germans had individual flak units that could reduce the chance of Allied success, with the downside of taking up a space in that area. (Since the Crisis in Command system only allows three units per space, and flak units could defend but not attack in ground combat, positioning flak required some tradeoffs.)

This was changed briefly in the “great streamlining” that happened when the game prototype came out on the iPad to a system where the Allies could just automatically interdict a single unit, much like the Axis did during clear turns in Drive on Moscow. But that felt too restrictive to the Axis (who were on the attack, and thus always had their best panzer unit affected) and a return to the old probability system felt right.

Even if these individual systems felt right, though, what about the overall game? Making historical wargames is ultimately about evoking a very specific sense of place that satisfies our sense of connection to the subject of our fascination. For me, wargames have always been about “touching history” in a way that books and films can’t, but are part of the same desire to inhabit this narrative space. How many times have I read a book or watched a documentary about some period in history, and immediately looked up what games exist on the subject?

Both previous Crisis in Command games were – above all – about armored breakthroughs. Take Col. Albert Seaton’s description of Operation Typhoon in 1941, from his book entitled The Battle for Moscow:

As German troops poured through the gaps there were frequent counter-attacks by T-34 and KV tanks which were particularly nerve-racking to the German infantry since the 37mm anti-tank gun had become, in their own words, little better than a museum piece. The German infantry corps, protecting the flanks of the panzer breakthrough, were marching hard in the wake of the tanks, great columns of men and horses cloaked with the all-pervading dust, each division stretching out as far as the eye could see, great winding snakes twenty miles long.

Enemy dead and dying lay in heaps where they had been caught in the machine-gun fire of German tanks, which by then were miles ahead. Abandoned equipment was everywhere, including American quarter-ton jeeps, never before seen by German troops. In two days the panzer forces advanced eighty miles, German casualties being very light. The fine weather held.

When you read that, and play Drive on Moscow, you get the feeling that the game really nails the history. The distances, the objectives, the pacing, all feel like the desperate, doomed thrust towards Moscow. But how can you take that same system and recreate the situation David Fraser describes in Knight’s Cross?

[Rommel] again attempted to advance with 21st Panzer on 13 July, and for once German coordination of tanks and infantry was faulty and the infantry, isolated, were broken up by enemy artillery fire with nothing achieved — an experience repeated on the following day. On 16 and 17 July Rommel just managed to check an Australian attack, also in the northern sector towards the Miteiriya ridge, by moving German units northward from the centre. On 15 July he had narrowly held an attack by the New Zealand Division in the area of the Ruweisat ridge, near the centre, and had counterattacked, but only regained part of the ground lost. This was becoming a battle of small-scale, often expensive, pushes and jabs by one side or the other and little opportunity for manoeuvre.

You really a really different feel from each battle. The drive on Moscow is like the punch from a fist of ice, with the fingers then spreading out to grab Moscow but rapidly melting, getting thinner and more brittle until they break. The desert battle is like a block of wood moving around on a field made of sandpaper, running into obstacles, changing direction, but always being worn down, until it is nothing but a nub.

The point of those two painfully awkward metaphors is that this kind of qualitative impression of game flow goes a long way towards perceptions of historical accuracy. But the early VASSAL versions of El Alamein felt very much like a desert version of Typhoon: the thrust into Ruweisat ridge led to a breakout nearly to the east edge of the board. After a few refits, the Axis had “Death Stars” of full-strength elite panzers and panzergrenadiers, which (due to the combined arms rules) were pretty much unstoppable in clear terrain.

Correcting this sort of imbalance can be challenging. There were all sorts of suggestions, from rearranging units to splitting the Ruweisat space in two. However, each of these remedies had far-reaching effects, and seemed like overkill when trying to simply correct an imbalanced first move.

Fortunately, the “persistent supply state” rule came to the rescue. In the latest iteration, the fact that individual supply is important not just for the current turn, but for future turns, the lack of a supply roll on Day 1, and an adjustment to the movement rules prohibiting armor from entering a deir except along a road or track (sounds reasonable!) all combine to prevent the Axis from ensuring good odds with a first-move attack on Ruweisat. Since the Allies can reinforce Ruweisat early, the game becomes very much a cat-and-mouse contest of incremental advance and positional fencing, always trying to consolidate position for the next short thrust. The game can also get very wild and confused, with combatants on all sides: exactly like the real desert battles.

Fortunately, the “persistent supply state” rule came to the rescue. In the latest iteration, the fact that individual supply is important not just for the current turn, but for future turns, the lack of a supply roll on Day 1, and an adjustment to the movement rules prohibiting armor from entering a deir except along a road or track (sounds reasonable!) all combine to prevent the Axis from ensuring good odds with a first-move attack on Ruweisat. Since the Allies can reinforce Ruweisat early, the game becomes very much a cat-and-mouse contest of incremental advance and positional fencing, always trying to consolidate position for the next short thrust. The game can also get very wild and confused, with combatants on all sides: exactly like the real desert battles.

There is still playtesting to be done, and the game has undergone further changes (like the streamlining of refits, and the change of offensive/refit periods to two-week blocks) but the fact that El Alamein (now renamed Desert Fox) recreates much of the character of the North African battle while still using the Crisis in Command system illustrates just how much development work can shape a game, long after the designer has constructed the framework of the game system. And, in the case of Crisis in Command, it illustrates just how robust that system really is.

___________________________________________________

*Desert Fox (El Alamein) actually has fewer spaces on the map than Battle of the Bulge. It’s the way the game plays that feels bigger.

** If you’re looking for one and only one book to read about the desert war I cannot recommend Correlli Barnett’s The Desert Generals highly enough. Written in 1960, it sought to refute the “Montgomery myth” that then-Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, Viscount of Alamein, had managed to propagate regarding his overall responsibility for the victory over Rommel. It describes the desert war from the perspective of the successive overall Allied commanders (in chronological order: O’Connor, Cunningham, Ritchie, Auchinleck, and Montgomery, with generous attention to Wavell as C-in-C Middle East) and is both informative and tremendously insightful. It’s also spectacularly well written, unlike much military history. It’s simply a pleasure to read, and if you have any interest in the subject, I very much doubt you’ll be disappointed.

***In boardgame parlance, the developer is the person who works with the designer to tweak, adjust, and in some cases overhaul the game system. Many boardgames have been saved, or dramatically improved, by skillful development.

No hexes, not a wargame!

Posted by Fred Zimmerman | May 5, 2014, 12:07 pmBruce, I came over here from Flash of Steel and am really excited to see your stuff collected—it’s always a highlight to see your name pop up on Three Moves Ahead or Quarter to Three. I’m sure setting up a website is giving you plenty of issues to deal with, but I was wondering if you could add an RSS feed? It would be great to be able to see new content as it pops up. Also, for what it’s worth, the website seems to be loading really slowly right now (using Firefox 28.0.)

Looking forward to more articles!

Posted by Ian | May 5, 2014, 12:52 pmYou can find the RSS feed here: http://www.wargamespace.com/feed/

Posted by Duder | May 5, 2014, 1:46 pmWhile there’s no RSS button on the site, the default WordPress feed is present. Go to:

http://www.wargamespace.com/feed/

Posted by Rindis | May 5, 2014, 3:20 pmGreat article, Bruce- maybe now they’ll give you that ride in the Studio’s Gulfstream 😉

Posted by DavidH | May 5, 2014, 10:19 pmBruce, tis good to see you have your own site now. Really looking forward to more wargaming/space ponderings from you – always valued.

Like the name of the site, its got a good ring to it!

All the best!

Posted by Ian Bowes (spelk) | May 6, 2014, 7:17 pmGreat article that truly identifies two of the interlocking challenges in wargame design: historical feel and balance.

I’m curious why the design team didn’t make the game about the entire North African war. Seems to me that the ebb and flow of the campaign with the far reaching armored thrusts would have been a better fit for the system and much more fun to play than the very tactical knife fight in a cupboard that was El Alemein.

Still, This should be an interesting game, and I’m looking forward to it.

Posted by Glenn Drover | May 14, 2014, 11:26 amThanks for all the comments, guys. I will put an RSS link on thepage if that helps, although it sounds like the default works too?

Posted by Bruce Geryk | May 18, 2014, 9:35 pmOne more small comment, will it be possible to “fix” the dates of your re-posted archival articles to when they were originally published?

It is sometimes possible to get an idea when they were originally posted or published contextually, but sometimes that information isn’t in the article.

Please keep putting new stuff up Bruce!

Posted by RickN | May 19, 2014, 9:20 amRick, I am not sure I actually know the dates when all the articles were originally published. What I am trying to do is put in sequential links so that people can page through the series in order.

Posted by Bruce Geryk | May 21, 2014, 4:14 pmThis is pure brilliant poetry! “The drive on Moscow is like the punch from a fist of ice, with the fingers then spreading out to grab Moscow but rapidly melting, getting thinner and more brittle until they break. The desert battle is like a block of wood moving around on a field made of sandpaper, running into obstacles, changing direction, but always being worn down, until it is nothing but a nub.”

Posted by SvenFu | June 8, 2014, 2:45 pmExcellent article, Bruce.

It’s very interesting to get a behind-the-scenes look at how these important decisions are made. It goes a long way to showing how a gaming system that some might dismiss as being superficial can actually capture the real flavour of a conflict.

I couldn’t agree more with your opinion of The Desert Generals; my dad gave me a copy of this about 30 years ago and I found it to be one of the most readable, succinct and insightful military history books I’ve ever had the pleasure to read.

Posted by Dave Bond | March 5, 2015, 9:02 am