If you love games, you owe yourself a read of Playing at the World, a wonderful history of tabletop gaming by Jon Peterson and published in 2011 by Jon’s own imprint, Unreason Press. It investigates the beginnings of the hobby we know as role-playing games, and in the process uncovers a lot of stuff I didn’t know about my beloved but now dust-covered board wargames.

Peterson does something interesting when it comes to the history of gaming, which is that he eschews personal narrative for an examination of the written record. While that is less remarkable in historical research, it hasn’t been applied too much to the history of gaming. A lot of gaming history consists of reminiscences and personal accounts, which are great, since not a lot that happens in gaming history needs to be rigorously examined or refuted. But that leaves it susceptible to misconception.

I talked to Peterson on a podcast about his book, and he explained that he had spent a lot of time (and money) collecting old fanzines, game memorabilia, and things that recorded the contemporaneous thoughts of important members of the gaming hobby in the early days of the pastime. I can imagine that this is a difficult and time-consuming yet ultimately straightforward task, since one you find the documentation, you can read it yourself. But what if it were freely available, but in a language you didn’t understand? And what if it were about something a little more important than the history of wargames and role-playing games? It would already have been uncovered and examined by now, right?

You would think.

The history of the Battle of Midway in 1942 has long been mythologized in American military history as the “turning point” that changed the war in the Pacific. With good reason. Before that battle, the Japanese had six functional fleet aircraft carriers. After the battle they had two. Given the disparity in industrial capacity between the United States and Japan, the gap in carrier strength could only grow bigger. So how it came to be that on a June morning in 1942, the bulk of the Japanese carrier fleet ended up on the bottom of the Pacific is a pretty dramatic story. The kind of drama perfect for narratives. And for gaming.

Playing wargames reduces some historical facts to lines in a rulebook. It’s one of the hazards of the pastime. One of them is that planes on an aircraft carrier deck are susceptible to dive bombing, while planes in a carrier’s hangars which are being armed are instead more vulnerable to torpedoes.

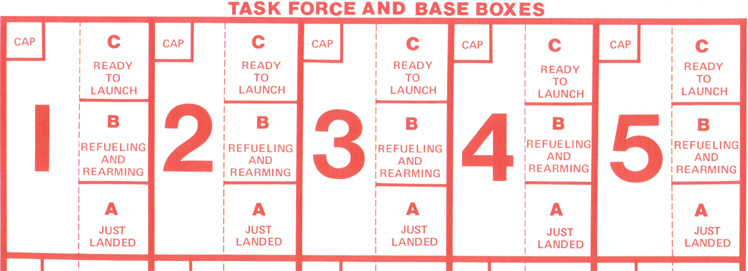

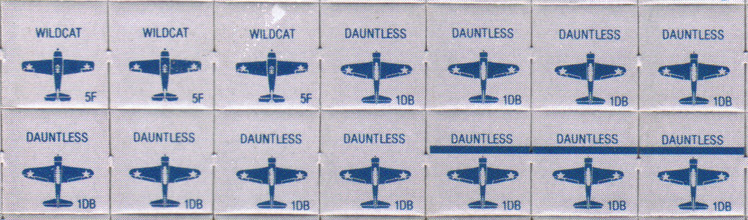

The late, great S. Craig Taylor, game designer extraordinaire, designed a pretty good game about Midway* entitled C.V. He came up with an interesting system for flight deck operations in which planes moved from box to box on a control sheet. Planes in the Readying box got armed with weapons, either bombs or torpedoes. They then got moved to the Ready box, which put them on deck and able to be launched. When the carrier recovered planes, they went into the Just Landed box, from which they could be moved to Readying.

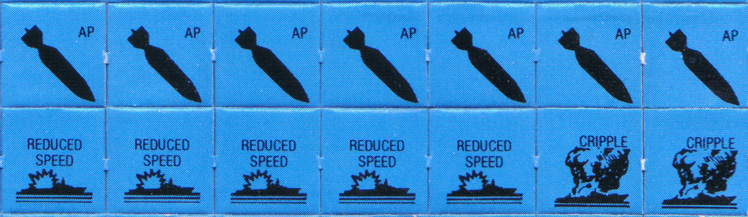

If you attacked a carrier and hit it with dive bombers, you doubled your hits if there were any planes in the Just Landed or Ready boxes. If you hit it with torpedoes, you doubled the hits if there were planes in the Readying box. It makes sense: planes on deck are going to get hit by bombs, whereas planes below decks in the hangar are going to be hit by torpedoes. Plus, this is what actually happened: during the Battle of Midway, the Japanese carriers had their decks loaded with planes, just “minutes” from launching a decisive strike on the American fleet, which by then had been spotted. Then, the famous American divebomber strike wrecked three of the four Japanese carriers. No torpedo hits were ever inflicted on the Japanese, but they had all their planes fueled, loaded, and on deck, which greatly increased the devastation. Just like the rules say. Factual.

But the assumptions in those lines sometimes aren’t applicable to the historical situation.

I grew up on two books about Midway: Walter Lord’s Incredible Victory (1967) and Gordon W. Prange’s Miracle at Midway (1982). Both were exhaustively researched, well-written, and as far as I know heavily influenced the direction of subsequent Midway research. Prange’s book, especially, coming on the heels of his critically praised and widely popular At Dawn We Slept, a frank analysis of the Pearl Harbor debacle with voluminous documentation behind it, seemed to settle the outstanding questions concerning America’s “miraculous” victory over the “overwhelming force” of the Japanese Combined Fleet in June 1942. These are pretty much the two major accounts that have shaped Midway scholarship in English since the battle happened. After that, I figured I had read about and pretty much assimilated everything worth knowing about the Battle of Midway.

Then I picked up a book entitled Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway.

I have two general rules about military histories: never buy a book with a question in the title, and never buy a book that claims to reveal “the secret of” anything. The subtitle of Shattered Sword sailed dangerously close to rule number two, but flipping through it, I noticed a lot of line drawings, diagrams, and course plots. That appealed to my quantitative side, so I bought it. And promptly learned that I didn’t really know anything about the Battle of Midway.

There are two intertwined assertions about the battle that have been propagated since the publication of Mitsuo Fuchida’s “Midway: The Battle that Doomed Japan” in English translation in 1955. Fuchida was the air group commander of the attack on Pearl Harbor, but famously was unable to participate in the Battle of Midway due to an emergency appendectomy just before the battle. Instead, he spent it on the Japanese flagship Akagi, which was sunk along with the entire Japanese main carrier force, although Fuchida obviously survived if he went on to write a book about it. He made several claims in his book, but two in particular have been carried forward through American histories — including Incredible Victory and Miracle at Midway — since then.

The first is that the Japanese would have spotted the American fleet thirty minutes earlier on the fateful day of June 4, 1942 if only the No. 4 search plane from the seaplane cruiser Tone had been launched on time. It was not, however, and was delayed instead by half an hour. This caused the American fleet to go undetected until too late.

The second is that when the decisive American dive bomber strike led by Lt. Cmdr. C. Wade McClusky struck the Japanese force and sunk three of the four carriers there on that same day, the Japanese were just minutes from launching their own strike, which would have caught the American carriers without their fighter cover (which had been sent with their own airstrikes).

The message? Thirty minutes and a faulty seaplane separated the Japanese from dealing the Americans a heavy blow which would have changed the calculus in the Pacific war. “We were that close!” was effectively Fuchida’s claim. And everybody bought it.

The authors of Shattered Sword, Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully, decided to investigate these “facts” through more than just interviews with battle survivors. Instead, they treated the battle to some extent as an event supported by various forms of objective data.** They use some impressive tools.

In addition to the details surrounding the carriers, we also draw heavily on the Japanese operational records of the battle. While it is true that the logs of the individual Japanese vessels were destroyed after the war, the air group records of the carriers survived. The tabular data contained in these reports (known as kodochoshos) has been used in some newer works to supply such details as the names of individual Japanese pilots. Yet, these records have never been used in a systematic way to understand what the carriers themselves were actually doing at any given time. For instance, knowing when a carrier was launching or recovering aircraft can also be used to derive a sense for the direction the ship was heading (into the wind), and what was occurring on the flight decks and in the hangars. Thus, we use the kodochoshos as tools to understand the carrier operations of 4 June in more detail than has been attempted previously.

They also use published Japanese sources that have never been translated, such as the volumes of the official Japanese war history series, which they state are “highly regarded for their comprehensive treatment of individual campaigns, as well as their general lack of bias.” They also use “never-before-translated Japanese primary and secondary sources, including monographs on Japanese carrier and air operations, as well as accounts of various Japanese survivors.”

As a physician and a scientist, I love data and objective analysis. As a writer and literature major in college, I love stories. In my experience, it’s rare to find a historical situation where the former goes so much in hand with the latter. Historical battle reconstruction is often an academic exercise with limited appeal, much like historical wargaming. The story of Midway is one where a painstaking reconstruction of historical events can lead to fundamental changes in the historical narrative. The hard data in effect writes a new story.

I should emphasize that the things I mention here are just a tiny fraction of what Shattered Sword addresses, and anyone interested in a singular account of a major battle that will likely change the way you look at military history from this point forward should buy and read the book him- or herself. It’s a brilliant combination of rigorous analysis and readable explanation, presented understandably and even more so, enjoyably. Their thought processes are logical and well communicated, and the documentary support is always presented clearly.

The whole “Tone search plane No. 4 was late” thing has always bothered me, because even the first time I read it, it didn’t make sense. If the plane took off a half hour late, then the ships it sighted had to have been in a different place than they would have thirty minutes earlier. So if the Tone No. 4 plane spotted the US fleet at 0745, can you say for sure it would have done so at 0715?

Parshall and Tully do the obvious thing, which is to plot the course of the American fleet against where they would have been if the No. 4 search plane had taken off on time. Of course, it’s not just a case of putting one overlay over another and saying, “Aha!” But based on their analyses of the search patterns, as well as radio traffic between the aircraft and the carrier fleet, and the plotted movements of the US task forces, the Tone No. 4 plane would not have seen the Americans if it had flown its assigned route a half hour earlier. In fact, according to the plots, the US fleet position was actually overflown around 0630 by the No. 1 search plane from the seaplane cruiser Chikuma. But it was experiencing heavy clouds and was only intermittently descending below the cloud level to check the ocean. It never detected the US carriers.

The significance of the late search plane depends on accepting Fuchida’s assertion that the Japanese strike was fueled, on deck, and within five minutes of being launched when the American divebombers appeared at 1020. Had the searchplane found the Americans at 0715, the Japanese strike would have been winging its way toward the US task force already, and the American planes might not have had any carriers to come back to.

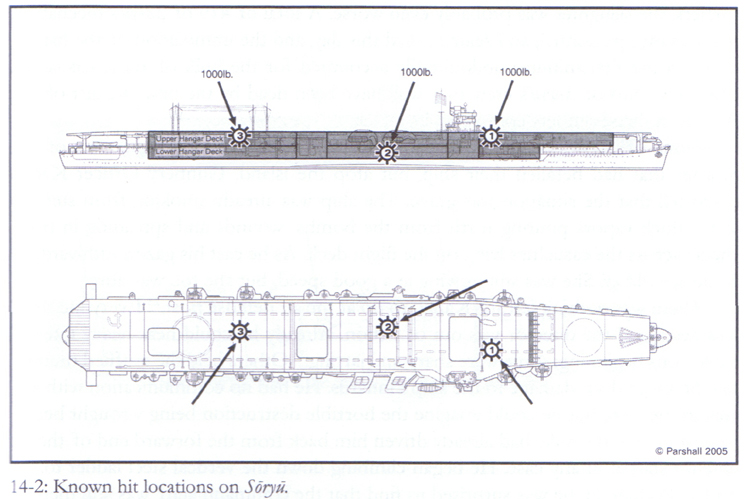

That’s one of the key myths of the battle that Parshall and Tully go to great lengths to dispel, and much of the book builds a convincing case that in fact the Japanese strike force was entirely below decks when the carriers were hit. They go through numerous sources and methods to ascertain this: an understanding of Japanese carrier operations to determine how long it would take to spot*** a strike on deck, the flight logs of the air groups on the Japanese carriers, which show almost continual launching and recovery of combat air patrol (CAP) up until 1010 on 4 June, which would have precluded the strike from being spotted at 1020 when the divebombers struck, and numerous Japanese sources, including the Japaneses official war histories (Sensi Sosho) published in the 1970s which did not support Fuchida’s assertion of a spotted strike on deck. Parshall and Tully go to further lengths to identify the likely location of this bomb hits on each carrier and compare this to the deck plans and aircraft storage locations to show that the many fires started by these attack were the result of armor-piercing bombs penetrating the flight decks and starting fires below.

SSG’s Carriers at War is probably the most accessible carrier battle game available on PC. It’s a bit inscrutable in describing its damage mechanics, though. All it tells you is that carriers are much more vulnerable with planes fueled and armed, and that hits can start fires which may then spread “based on the ship’s damage control rating.” I wonder if hit location has anything to do with it.

But the whole basis for the damage model in the C.V. series is that bombs hit the deck and have their hits doubled if there are planes in the Ready/Just Landed boxes (on deck) and torpedoes double hits when planes are Readying (below decks). It’s a major consideration in game strategy. In Victory Games’ innovative solitaire game Carrier, released in 1990, the rules explaining surprise have this “Design Note” in the main rulebook explaining the design decisions.

In its worst form, [surprise] could mean being struck with planes on deck. The latter was every carrier admiral’s nightmare. A group of fuelled-up, bombed-up planes amounted to a mass of explosives ready to be touched off. In such a situation one bomb could transform the carrier into a blazing ruin – as happened to the Japanese at Midway.

“Being struck with planes on deck.” You know a military history meme has buried itself deep when the ultra-historically minded people who write wargame rules are using it as justification for their game mechanics in a design note.

Parshall and Tully make a convincing case that Fuchida’s account was incorrect in critical ways. It’s a spectacular revelation, and you would think that’s the end of the story, but even though it hardly seems possible, it just gets better. They had apparently been collecting doubts about Fuchida’s account for years.

[I]t was a conversation between the authors and John Lundstrom**** that crystallized the matter. Lundstrom had noticed, in one of those rare epiphanies when the obvious suddenly reveals itself, that the photographs taken by American B-17s over [the Japanese carrier force] on 4 June showed completely empty flight decks on three of the Japanese carriers at around 0800. What did that mean? To be sure, the pictures were taken more than two hours before the American attack, but it caused Lundstrom to pose an interesting question. Had Nagumo’s reserve strike force ever been on the deck at any time during the battle?

It’s that moment, the authors say, which led them to undertake the investigation that resulted in the discovery about Fuchida’s inaccuracies.

As with any historical discovery that substantially deviates from the accepted scholarship, Parshall and Tully made efforts to confirm their research by seeking input from Japanese scholars who would be familiar with the very Japanese data they were interpreting.

[S]eparate inquiries were sent to two knowledgeable Japanese sources, politely asking for their insights on the matter. This was done in an extremely circumspect fashion, on the assumption that Fuchida was still held in high regard in Japan and not wanting, as foreigners, to appear disrespectful towards a famous war hero.

To their surprise, their Japanese sources completely dismissed Fuchida’s account. This is quoted as part of the reply Parshall and Tully got from their Japanese correspondents, and is one of my favorite paragraphs in a military history book, ever.

To tell why Fuchida’s book contains transparent lies, it’s necessary to explain the background of the time it was written. Until around Showa 27 (1952), Japan’s speech and writing was under … censorship … so they could not say what they wanted. However, since around Showa 28 (1953) … “Cheering up” memoirs by mainly former military personnel were rushed out … Of course, the mental pressure of those who were truly incompetent and responsible, and who tried to conceal their own faults, gave strong effect as well [sic in original -bg]. Fuchida’s Midway or Kusaka’s Kido Butai that came out almost simultaneously, could be regarded as nonsense books which were meant to conceal failures and incompetencies of such kind, and to protect each other. If they are still among the few books available [on the Battle of Midway] that have been translated into English, it’s a funny story.

“Transparent lies.” Translation: Ha! Joke’s on you, America! Stop relying on eyewitness accounts!

And learn Japanese.

I was reading Craig Symonds’ book The Battle of Midway, published in 2012 as part of the Pivotal Moments in American History series by Oxford University Press, for the 70th anniversary of the battle. At the end, in “A Note on Sources,” he makes this extraordinary acknowledgement of Shattered Sword.

Both Walter Lord and Gordon Prange conducted a number of interviews with Japanese survivors of the battle (often using intermediaries) and incorporated their views in their excellent histories. But among the sources in translation, the most influential was a memoir by Mitsuo Fuchida (with Masatake Okumiya) published in America as Midway: The Battle that Doomed Japan, the Japanese Navy’s Story (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1955). Fuchida, a naval aviator who had led the attack on Pearl Harbor, was also to have led the air attack on Midway, and would have done so except for an untimely bout of appendicitis. Because of that, he was instead an interested and knowledgeable spectator on the bridge of the flagship Akagi during the battle. Because of the dearth of Japanese sources, and because of the persuasiveness of Fuchida’s firsthand account, it had a tremendous influence on Western narratives of the battle. Alas, as Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully demonstrate in their book Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005) Fuchida had an agenda of his own, which was to suggest just how close the Japanese had come to delivering a coup de grâce against the Americans, and as a result, not everything in his book can be taken at face value. Parshall has charged that “it is doubtful that any one person has had a more deleterious long-term impact on the study of the Pacific War than Mitsuo Fuchida.” (Parshall, “Reflecting on Fuchida, or ‘A Tale of Three Whoppers,'” Naval War College Review 63, no. 2 (Spring 2010) 127-38. Whatever the merits of that statement, Parshall and Tully made an immeasurable contribution to the historiography of the Battle of Midway by delving into the Japanese accounts and analyzing the battle from the perspective of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Parshall and Tully’s book was published in Two Thousand and Five. It has taken that long to correct the scholarly record in English of America’s Pacific-War-defining battle that took place in 1942.

Maybe more people should study Japanese.

And update the C.V. rules.

———————

*Taylor used the same system in one of my favorite boardgames of the early 1980s, Flat Top, to depict the Solomons carrier battles.

**The authors treat the historical event of the battle with a tremendous attention to its complexity, and they acknowledge that many of the things that they address may not be ultimately knowable (like Admiral Nagumo’s thinking at a particular time). But their rigorous attempts to fit the description of the battle to the existing data and what is known about Japanese carrier operations and doctrine is truly remarkable, in my opinion.

***Spot is a term for moving aircraft onto the flight deck in preparation for launch.

****Lundstrom is the author of First Team, a landmark study of air combat in the Pacific War.

Read Jonathan Parshall’s essay mentioned above here.

Parshall also has a website at www.combinedfleet.com

Can I just study the part of western civ that relates to imperialism in India/Vietnam/Algeria/Tunisia/Operation Ajax?

Posted by due date | May 8, 2014, 8:48 pmThanks for yet another great article, Bruce! It’s always a pleasure and an education reading your well thought out and researched and entertainingly written pieces. I’m very glad they have a more permanent home now as they markedly enrich our shared gaming and historical hobby environment. May your planes always be spotted at just the right time.

Posted by Jarmo | May 15, 2014, 12:11 pmTerrific article, Bruce! I’m glad I finally had the opportunity to read it.

One nitpick: The 1,000 pound bombs the American SBDs sank the Japanese carriers with were general purpose bombs, not armor-piercing. They didn’t need to be armor-piercing, because, like their American counterparts, the flight decks of the Japanese carriers weren’t armored. The gp bombs simply smashed right through the wooden flight decks and set off fatal conflagrations on the hangar decks. This gets to a problem I had with C.V.’s hit doubling system long before I read Shattered Sword. The hangar deck of an aircraft carrier is directly under the flight deck, well above the water line. So why would a torpedo do double damage to an aircraft located there? On the other hand, as Midway demonstrated, a wooden flight deck offers little or no protection from plunging bomb damage.

Posted by Jason Levine | January 29, 2015, 12:20 amThen that is another knock against the game system, because in C.V. and Flat Top the GP bombs are useful against ground targets, but less useful against ships!

Posted by Bruce Geryk | January 29, 2015, 10:53 amIf you’re trying to catch the enemy carriers with their flight decks loaded with planes, as the Americans were (and Fuchida said they did), you don’t want to use armor-piercing warheads, because they won’t explode among the parked planes. They will plunge right on through to the bowels of the ship and possibly go all the way through the ship’s bottom. You want to use gp bombs that will explode among the parked aircraft and ordnance, shatter the wooden flight deck and wreck havoc on the hangar deck as well.

Posted by Jason Levine | January 29, 2015, 3:09 pmBruce, Fuchida did two accounts of Midway, one in 1951 (Battle That Doomed Japan), the second in the 1970’s (For That One Day, 2011). Fuchida’s 1955 book outlines a battle lost by command failures – Yamamoto and Nagumo’s HQ threw away the battle with lousy planning, coordination, and execution. Fuchida wasn’t so much interested in the nuts and bolts of aircraft cycling (deck ops) because deck ops were a routine fact of carrier operations well known to 1st Air Fleet HQ.

Re – Tone 4. Fuchida’s account dwells at length on the errors made in the command decisions related to the search failure – prebattle intel (inadequate and poorly distributed) the scale of the search (inadequate) and the method used (inadequate and tactically inappropriate). That Nagumo was unlucky in his search “roll” after he and Yamamoto made all these bad decisions was not as important, (had Nagumo acted correctly then the density and timing of his search would have prevailed).

Fuchida took aircraft cycling into account because he believed the fatal error that lost the battle was the decision to rearm with torpedoes after 0830. He thought it was better to attack with the torpedo bombers armed with 800kg bombs than risk the delay of rearming. Hindsight? Perhaps, but either way he addresses the decision made 30 minutes AFTER the Tone 4 report was on the bridge of the Akagi.

With respect to the bombing of the Japanese carriers, Fuchida’s 1951-55book states that one carrier – the Akagi – was about to launch. Soryu, according to Fuchida was still moving strike aircraft into launch positions, preparations not yet complete. (Egusa may be his source on that as they were in hospital together after the battle). In Kaga’s destruction Fuchida mentioned nothing about any strike aircraft on deck – there were no aircraft mentioned on her flight deck in Fuchida`s account of her bombing. With Hiryu, Fuchida stated it launched on Yamaguchi’s authority at 1040, not at 1025.

Shattered Sword presumed that IJN doctrine always had the carrier launch in unison since this was the preferred method, (the Midway strike was about a 4 minute gap, for example). But this was not ALWAYS the case. At Darwin different squadrons of the same 188 bomber strike wave were launched up to 30 minutes apart, (the force did a running rendezvous with the first half waiting in orbit until the second half commenced launch, then departed and the dive bombers caught up en route). In the Indian Ocean during the sinking of two British cruisers Akagi launched its dive bombers to orbit about 10 minutes before Hiryu started, and 14 minutes before Soryu launched. At Midway, Fuchida did not know the status of the other carriers and did not claim it. That Akagi was going to launch meant nothing – her planes would wait in orbit, just like at Darwin and in the Indian Ocean.

Two sides to every story….

Glenn

Posted by Glenn McMaster | August 3, 2017, 4:58 pm