[The War in the East game diary is an intermittent, long-running series I started in early 2011. The first part covered Operation Barbarossa. The second covers Operation Blue and the Stalingrad campaign. If you need to catch up, you can go to the series list, where the most recent articles are listed first.]

It has been a while since the last one of these, but the great thing about wargaming is that it’s really a process, as I hope this series of articles has shown. And the longer the process goes, the more time it has to make all sorts of connections between things that may not have happened then, but happened later, after the time you probably should have been writing. It turns out that the longer you procrastinate, the more stuff you read, and the more interesting stuff happens.

One of my favorite observations about the historiography of the Eastern Front was by Unity of Command designer Tomislav Uzelac, who commented that in many histories, it seems that the Germans somehow magically arrived at Stalingrad “as if by bus.” Which immediately made me jealous, because although I presumably know English at least a little better than Tomislav does, it’s the kind of clever turn of phrase that sounds like it could only have come from a European.

In addition to being clever, Tomislav is right. The story of how the Germans got to Stalingrad is complicated, and even though I’ve written five posts so far in this Stalingrad series, it still might not be clear what happened. And – like I said – it has been a while. So consider the next paragraph to be like that thing at the beginning of The Fellowship of the Ring where you learned about Isildur’s Bane.

The campaign of 1941 cost the Germans manpower and materiel that they would never recover. As a result, they couldn’t mount an offensive all along the front like they had done the previous year. They (that is, Hitler) settled on an offensive in the south, but even that was too ambitious for their reduced capabilities. The resulting plan was a stepwise one, codenamed “Blau” (Blue) and had multiple phases. Blau I was a push towards the industrial city of Voronezh on the Don River. Blau II was a continuation in the form of a push down the west bank of the Don meant to encircle the Soviet forces there, and Blau III was a southern pincer movement through the city of Rostov on the Black Sea (actually the Gulf of Taganrog) launched to meet the northern pincer created at the end of Blau II. It’s all a bunch of codenames and placenames, but the fact that it took the Germans three phases to execute the plan instead of just launching a massive attack like they did in 1941 shows just how degraded their capability had become.

The plan changed several times, but what ended up happening was that the planned encirclement battles didn’t yield the expected number of prisoners. This (and other factors) led to a debate among historians as to the actual narrative of the prelude to Stalingrad, and a sort of myth developed about the Red Army withdrawing into the vastness of Russia, drawing the Germans to simply follow after them to their ultimate defeat, “as if by bus.”

David Glantz has written a “Stalingrad trilogy” (pictured above) that now runs over 2,100 pages. If you look closely at Volume Three, you’ll notice it is subtitled “Book One.” I guess “Stalingrad Trilogy” is too catchy a title to discard on a technicality. As you might expect, he has some things to say on the subject of the Fall Blau (Plan Blue) operations, that commenced in late June 1942:

Previous histories of Operation Blau have argued that Army Group B’s dramatic advance to the Chir and Army Group A’s equally significant advance to the lower Don [Both are rivers. –bg] at and east of Rostov were virtual “cakewalks” because Stalin and his Stavka simply ordered the forces of Southwestern and Southern Fronts to withdraw out of harm’s way rather than defend the region. As a result, they describe the fighting during Blau II as desultory. As a corollary, they fault the German army groups for permitting the Soviets to withdraw and thus avoid the immense losses they had suffered during encirclement in Operation Barbarossa the year before. These judgments are only partially correct.

Although the German advance was indeed dramatic, closer examination of events during Blau II indicates that the operation also involved intense, if episodic, fighting, particularly in the Millerovo region, because, as the directives he issued indicate, Stalin insisted that his two fronts conduct a determined defense rather than a general withdrawal. To the credit of German commanders who orchestrated the offensive, this Soviet defense clearly failed – however, not because the Red Army chose to withdraw rather than fight. Moreover, Germans’ failure to reap the fruits of victory by taking tens if not hundreds of thousands of Red Army prisoners as they had in 1941 did not mean that the Soviet forces in the region escaped unscathed, ready to fight another day. In fact, most of the armies of Southwestern and Southern Fronts, that became wholly or partially encircled in the eastern Donbas and Rostov regions, including 28th, 38th, 9th, 12th, 37th, 18th, 56th, 24th, and 57th, were either virtually destroyed or survived as mere shadows of their former selves.

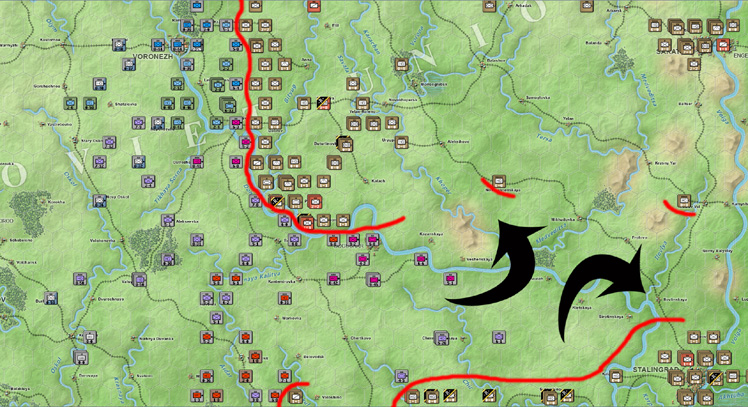

My experience in War in the East is that the AI keeps forming defensive lines just out of the reach of my armor, which struggles to stay supplied as the panzer spearheads strike out into empty space. In the screenshot below, the Soviets have huge holes in their line, which I could easily exploit with the black arrows I’ve drawn, if I had any units where those black arrows are. But I don’t. You can see Stalingrad just at the southeast (lower right) corner of the map. By the time I can get enough units there, the Soviets will have built a front behind that wavy blue line bisecting my black arrows. That happens to be the Don River. In the meantime, I have a lot of unit movement to take care of.

Turns now consist of pushing units as far east as I can each turn, trying to preserve command structures, keep supply chains intact, and basically prepare for the combat that is going to happen three or four turns (weeks) from now. So my experience could definitely be described by previous histories as “desultory.” And it’s this monotony, the seemingly endless trek across distance that is little more than empty space, that has come to be considered a “bus ride.”

That doesn’t mean these days and weeks aren’t documented. One particularly interesting source is by a guy named Jason Mark, whose work figured prominently in a previous post about the Advanced Squad Leader module, “Kampfgruppe Scherer.” Mark is not exactly a historian, and his works are only partly histories. He is more of an archivist, and many of his books are more properly personal testaments: archival evidence of the lives and humanity of the participants in the total war of the eastern front, made possible only through close cooperation with the participants’ families. His book about the siege of Cholm is an impressive and personal chronicle of a battle that was a sort of microcosm of the entire eastern front, little-known as it was. Island of Fire, a painstakingly detailed description of the battle for the Barrikady Gun Factory, is essential reading for anyone trying to come to grips with the specifics of the fighting there (or maybe trying to design a game about it). Probably needless to say, I own a lot of books by Jason Mark.

One book I bought almost as an afterthought is called Into Oblivion: the 305 Pioneer Battalion. It documents the progress of pioneer battalion of the 305th Infantry Division (“Bodensee”) as it is transferred from garrison duty in France to the eastern front and then marches across miles and miles of Russia to the meatgrinder of Stalingrad. It was made possible almost entirely due to the fact that Mr. Mark was able to track down the daughter of one of the battalion’s company commanders, Richard Grimm. The way in which these records became available is worthwhile reading in itself. But the book is an exquisitely arranged set of details, some more mundane, others less. A picture of the officers visiting a baroque cathedral in Germany prior to their transfer to the east is included. As is a picture of a soldier relaxing on a captured British Bren carrier inside Russia. And, of course, bombed-out buildings in Stalingrad. All assembled into a careful chronicle memorializing the journey of a bunch of soldiers deep into a country where they had no business at all.

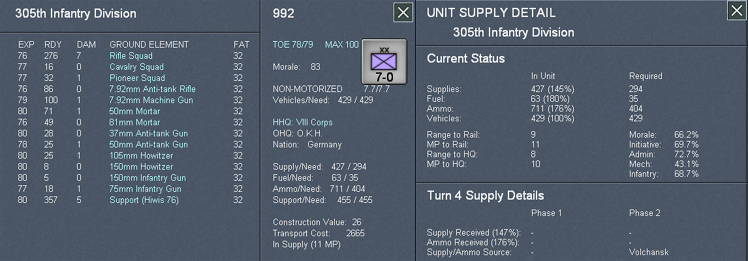

You can find a lot of detail in War in the East, too. Here is that same 305th “Bodensee” Division, currently about 70 miles west-northwest of Boguchar, on the west bank of the Don. It’s in pretty fine fettle, if you take a look at the numbers. Oh, look: there are 32 squads of pioneers! That’s our battalion, right there. They have all the supply, fuel, and ammo they need, and then some. Their morale is “83.”

I looked through my copy of Into Oblivion, trying to find some letter home in which Richard Grimm quantified his morale on a scale of 1-100. I couldn’t find one. I did find some other things, though, that made me think immediately of War in the East, Operation Blue, Turn 4.

Into Oblivion is very much Richard Grimm’s experience of the almost unimaginable. Much of it comes from letters home, in which he describes various events, whether it be rebuilding a bridge (his battalion was one of pioneers, which essentially means engineers), scouting out a river crossing, or clearing out a pocket of Soviet resistance. Furthermore, Oberleutnant Grimm is a meticulous note-taker. Into Oblivion has a chapter entitled “Easy Victories, Long Marches” that pretty accurately describes the current phase of this scenario.

I had the task of getting my company to a command post. After I crossed over a creek, ahead of me was a vast, slightly undulating countryside, without trees or anything in the distance on which I could get a bearing. All that could be seen was earth. I knew which point I had to aim for on the map, so I set the march compass and reached my point exactly after going cross-country for sixteen kilometres. No road, not even the most primitive dirt track or anything else, was available as an orientation point. The fields, especially the untilled ones over which no vehicles have driven, are the best roads here.

I’m pushing a purple-and-grey square representing Grimm’s division across a green map helpfully demarcated with hexes, so that I never have to click a box to set a march compass, or select a menu item defining just how many kilometres I was going to trek cross-country. But I’ve had this sense of digital drudgery ever since I completed the initial encirclement battles And it’s telling how often Grimm returns to this idea of the space and distance of Russia.

So, last night I arrived at my staff a hundred kilometres behind my company front so that I could personally take mail, rations, market goods, etc. back to the front. On a sixty kilometres stretch of road there is neither a house nor a village for as far as the eye can see. I also celebrated a jubilee, one thousand kilometres linear distance according to the map, mostly on foot, a tiny part on horseback, but all on Russian roads. Don’t ask about other distances. Behind us we have marches in over thirty degree heat in the shade for the last ten days.

Into Oblivion isn’t just about Grimm’s experience, and there are numerous letters, photos, and descriptions from many members of the battalion, as well as higher ranking officers. Mark also uses outside sources, but tends to stick to primary German accounts, like official battle histories and the like. But the account is very much colored by Grimm’s experience, and you can see the overwhelming effect of the space of Russia over and over in his letters home.

The terrain here is very monotonous. The fields are not cultivated and the wheatfields are full and grown through with grass. There is nothing but these fields as far as the eye can see, perhaps a small row of bushes about ten metres long after twenty kilometres. Deep, almost impassable gullies cut through the terrain and they can only be spotted when they’re right in front of you. Of course, these often prove to be obstacles and lengthy detours are needed. Otherwise you can march a hundred kilometres without running into an obstacle.

Much of the action that Grimm and his comrades describe is beyond the scope of the game: bridging operations that are too low-level for War in the East, mine-clearing jobs that would probably only be relevant in a game of Advanced Squad Leader with 40-yard hexes, not ones that are ten miles across. But once again, at its chosen level, War in the East conveys an essential reality about the campaign it portrays: immense space, elusive defenders, and the desultory bus ride towards an eventual, terrible reckoning.

But people play wargames for the war, and Jason Mark also seems to understand that a war book needs some dramatic battle descriptions. He even borrows one from Wolfgang Werthen’s 1958 history of the 16th Panzer Division:

Heavy tank forces were facing each other on both sides of the front. They surrounded each other and were trying to encase each other. The size of the field of operations was 100 x 100 kilometers. There was no front. Like destroyer and cruiser forces at sea, the tanks were fighting on the sandy seas of the steppe, struggling for favorable gun positions, driving the opposition into the corner, holding the fort for hours on end or locations for days, breaking free, and turning around and chasing again after the enemy. And while the tanks were clawing at each other in the overgrown steppe, the air fleets were fighting in the cloud-free sky of the Don, fighting their opponents in the hiding holes of the balkas [dry river beds –bg], blowing ammunition supplies into the air, and setting fuel supply columns on fire.

As if on historical schedule, we’ll be getting into exactly that next time.

_________________

If you’re wondering whether you’ve been away so long that you don’t recognize the War in the East maps and counters, the difference is that I’ve installed Jison’s spectacular MapMod. It wasn’t available in its totality when I was doing the Barbarossa scenario, and the difference is immediate and obvious. I love the fact that there are talented and committed modders out there improving already excellent products. If you play War in the East, this mod is essentially a requirement. It even spruces up the interface!

Argh. Just what I need: A reminder that I really want to try this game someday.

😀

Posted by Rindis | August 13, 2014, 1:00 pm